By TwoCircles.net Staff Reporter,

With the killing of Pulitzer Prize-winning German photographer Anja Niedringhaus in Afghanistan on April 4 in 2014 during the election coverage has once again revealed the vulnerability of journalist working in conflict zones. The Associate Press photojournalist was shot dead by a gunman in her car in which another journalist was also injured. In 2013 alone more than 70 journalists were killed across the globe and the scene continues to be similar.

Keeping that in mind TwoCircles.net brings to its readers a hair rising story of a photojournalist who returned back from the jaws of death to tell his story. His name is Altaf Qadri and he too works with the Associate Press, who went missing for more than 48 hours during the Libyan revolution –armed conflict between the forces loyal to Colonel Muammar Gaddafi and those seeking to oust his government in 2011.

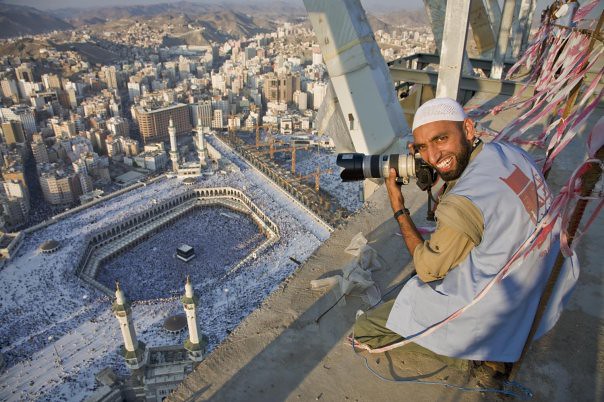

Altaf Qadri during his assignments in various places.

One of the luckiest survivors was award winning photojournalist Altaf Qadri of Kashmir who went missing on April 9 in 2011 leaving all his fellow journalists and others in shock while he was covering the civil war.

Qadri was always interested for such assignments since the day he took photography as profession from being a computer engineer 2001.

So, he was thrilled to cross to the Libya border on March 29 in 2011 through the Egyptian land port of Salloum, the main border point between Egypt and Libya. After spending the first night in Tubruk, a small coastal town in eastern Libya, he headed towards Benghazi. This was regarded one of the best routes for foreign journalists to reach Benghazi as it was under the control of journalist-friendly rebels.

The Battle of Brega–Ajdabiya road was one of the many battles during the Libyan revolution between forces loyal to Muammar Gaddafi and the rebels, for control of the towns of Brega and Ajdabiya respectively and the Libyan coastal highway between them.

“It was Saturday morning, April 9 when I along with other AP staffers finished our breakfast and were about to leave for the volatile frontline between Brega and Ajdabiya some 140 km from Benghazi, where we were based. Our routine was to head to the frontline in the morning, file from Ajdabiya and then head back to Benghazi by evening. Eventually the cars left Benghazi hotel at around 7.30 am. It is a pretty long drive from Benghazi and at even 150 kmph it would take an hour and a half to reach the frontline as we drove along the desert which was dotted with the remains of tanks and other military vehicles. Suddenly, my mind went to the four New York Times journalists, including photojournalists Tyler Hicks and Lynsey Addario, who were captured by Gaddafi’s forces the previous month. They were brutalized for four days before being freed. However, everything looked ‘normal’ that morning,” Qadri said.

It was around 9 am when they reached the town of Ajdabiya, the last Libyan town held by the rebels in the east, some 80 km before the frontline. They crossed one of the many checkpoints manned by the rebels on the way to the frontline which was at a gas station and a mosque that marks the halfway point between the Libyan towns of Brega and Ajdabiya.

At about 10 am, Qadri noticed some rebels loading grad missile into a red pickup truck with a launcher mounted on the back. “I thought I would take some photographs while they launch them towards the Gaddafi’s forces’ positions. The rebels looked familiar so I went ahead and asked them, mostly by sign language, if I can accompany them, and they agreed reluctantly,” he said.

When he climbed on the back of the truck, he thought Cairo based AP photojournalist Ben noticed him but nobody actually seen him leaving with the rebel truck. He was lucky to pass that check point in the disguise of a rebel as no journalists were allowed beyond that point.

He was thrilled. “I was about to see live action at the frontline. I am sure given a chance any journalist would have done the same,” he quipped.

At the Ground Zero:

The action had already started at the ground zero as the truck advanced for about a kilometer then went off the road into the desert and behind a sand dune. The rebels fired four grad missiles then drove back toward the main road to reload. They then returned behind the sand dune and fired two more rockets.

All of sudden their truck came under heavy return fire. Panic broke. Shells, fired by brigades loyal to Gaddafi, started falling all around them.

Then came the most crucial moment – “There was also heavy machine-gun fire so a rebel and I jumped in the back of the truck. I was sitting right beneath the grad missile launcher. The rebels fired a third missile as they were speeding away and the blast knocked me off. I fell on the sand with a thud,” he said.

He tried chasing it but it sped away. “One of the rebel who was on the back looked at me and tried to tell the driver to stop, but they were too scared to stop, even for two seconds, because Gaddafi forces were apparently more closer to us than I had thought. Forces were using heavy machine guns as they were closing in. Suddenly I found myself being deserted amid a rain of bullets and bombs,” he said.

Bullets continue whizzing through the air and hitting the sand nearby while Qadri ran for his life. “I was wondering why none of these bullets hit me. I rolled down the sand dune and ran back to the gas station, which was still about 500 meters away. By the time I got there, all the rebels and journalists had already fled, including the AP team I was with,” he said.

Suddenly he was all alone amidst the sand and bullets. After reaching the gas station he started to search for a place to hide or he would be targeted by the Gaddafi forces.

“So I ran behind and found three storerooms, a toilet and a small dark room with a shattered glass door. My only option was that dark small room, with a shattered glass tinted door. The door was locked so I crawled into the room from under the shattered tinted glass. It was a very small room, but dark to my advantage. It had been used as a kitchen before. There was a portable gas stove. I lifted the lid of the stove to further darken the room and placed it just near the shattered part of the door so no one could see me inside. All this while, gun shots and grenade blasts were drawing closer and closer,” he said.

Then after, Gaddafi’s forces were rushing towards the back of the gas station hunting for rebels. They were going along the storerooms behind the gas station and kicking the doors, then firing their guns inside. They finished three rooms already, now it was the turn of the small room Qadri was hiding in. “I could hear them walking towards the room. I could hear the shattered pieces of glass door being crushed under their boots as they walked towards my room. I was sure they’d shoot me than ask for identification. I said my prayers, remembered my family and asked Allah for forgiveness. All of a sudden they stopped just near the door, discussed something in Arabic for a few seconds and retreated back to the front of the gas station without firing a single shot into the room. What a relief as they walked away. I took a deep breath and thanked Allah, the Almighty,” he added.

So, it was the place he has to be for the next couple of days until he finds some option to get out safely. It was a very small room — 4×6 sq. ft. with a steel kitchen sink and a small window opening towards the storerooms and a huge wall. The room was stinking of rotten onion and human excrement in one corner, an empty plastic bottle and two steel plates etc.

“I found a piece of cloth which I put over the window to make the room even darker and to hinder the view from outside. I took my compact camera and started filming the room, briefly. I disabled all the alarms and reminders from my mobile phone to ensure there’s no noise. I replaced my used camera flash cards with blank ones and hid the used ones in my boots,” he said.

By that time, his legs were numb as he had been crouching down on the floor for a pretty long time. Many scary thoughts crossed his mind — he was more worried about his family and started looking at the photos of his family and friends stored on his mobile phone which encouraged him not to give up.

He kept on thinking about Anton Hammerl — a South African freelance photographer who went missing after coming under fire from Gaddafi forces near the frontline just a few days ago on April 5.

“I recalled when I offered him a ride in my car to the frontline, just two days before he went missing. We spent a complete day at the frontline. I could see he used to push his limits to get a perfect shot. While riding a rebel truck we video-graphed each other, some of which are still with me. He talked about photography, his family and his newborn baby, Hiro. The Libyan regime repeatedly told Anton’s family that he was alive and well. The truth was that Anton was killed on the very first day. But the Gaddafi regime knew about Anton’s fate but chose to remain silent. I asked myself, am I also going to meet the similar fate?” he said.

For five hours he continued to be in the same state. There was an urge to urinate but he could not take a chance to urinate on the floor because if it flows out, anybody could see it. So he did it in a plastic bottle.

At dust when all was quiet he crawled out of the room and peeked from the corner of the gas station. As nobody was nearby he explored those storerooms which were raided by the forces earlier in the day.

In the meantime he saw a group of newly built houses, through a steel mesh window of one of the storeroom, at a distance in the desert. “I thought it would be a good idea to stay in one of them, after dark. I went back inside the small room and waited for some more time. When it was dark enough, I ran away from the room towards this group of newly built houses which was a few hundred meters away from the gas station. I decided to stay in the middle one to be safer,” he said.

He was scared suddenly after entering the dark room that he might run into the forces. In the fifth room he found two mattress, two pillows and a blanket. It appeared that fighters from one of the sides had squatted in the house. There were empty bottles, empty cigarette packets and food wrappers scattered about.

By then he was damn tired and thirsty. Luckily he found some drinking water in a plastic bottle lying in a corner with other trash and an unfinished small mango juice packet, though it was too little compared to his thirst.

“I started contemplating my next course of action. I thought of making my way back to Benghazi, which was more than 150 km from this place, in the cover of darkness, but that seemed foolhardy since I could be mistaken for an enemy by either of the two sides and moreover walking such a distance in desert at night was crazy. I could hear heavy military vehicles and tanks moving towards Ajdabiya. So I decided to stay put unless there was a real opportunity,” he said.

The award winning photojournalist later said that it was perhaps the loneliest night of his life. “I was probably only unarmed man in an area of 150 sq. km. I fell asleep at about 1 am, but often woke to the sound of NATO aircraft on reconnaissance mission, for a half-hour period about every two hours. A loud bang woke me up at around 5 am,” he said.

NATO aircraft had finally started bombing the Gaddafi’s forces’ positions from Brega through Ajdabiya.

As the airstrikes ceased just before noon, he decided to take a look outside and see if there was any chance of finding a safer place or even if he could escape through the desert. He sensed of getting his lost hope back as he noticed a herd of camels outside.

“At this point, I thought of disguising as a camel herder but that sounded stupid. I decided against venturing out as the road was very close to the house and there was continuous movement of military vehicles. So I went back to the house. I remained in the house all day, watching from the windows as Gaddafi’s forces drove up and down the road,” he added.

At around 2 pm, he saw a group of soldiers, who stopped by at the gas station, eating and resting. And then some soldiers rode a pickup truck and started patrolling near these houses to make him more panicking.

But there was little he could do. Fortunately, they drove past this house without stopping and headed back to the gas station.

The Final Hours:

At 5 pm, he saw normal pickup trucks arriving from Ajdabiya at the gas station, some of them with the rebel flag. It seemed to him that they were rebel trucks captured by the Gaddafi forces.

In the meantime, one of the trucks drove near the house to increase his heartbeat. Then he heard men talking outside, then heard someone opening the front door. He thought there is little hope of survival.

“I stood just in front of the closed door holding my cameras up so the man would see them before reaching for his gun,” he said.

As soon as the man opened the door he yelled ‘sahafi, sahafi’ – ‘journalist’ in Arabic. “He was dumbstruck. Before he could say anything I started to communicate with him through sign language so that he could be sure that I was a foreign journalist and hence no threat to him,” he said.

He led Qadri to the pick-up parked just outside the gate as other armed men in the pick-up truck pointed their guns on him.

He gave Qadri a cheese sandwich and an orange juice bottle while making me sit in the pickup when he gestured that he was thirsty.

He thought the forces were not as barbaric as they were being portrayed. “I couldn’t eat the sandwich due to my dry throat and may be because I was nervous. I was holding my passport so that I could show it before their commander asks for it,” he said.

He narrated whole story and showed passport. The commander put it in his pocket and said, “Don’t worry we’ll take you back to your hotel but you have to say in front of the camera that we saved you”.

He thought they would shoot him after this. But at the same time he felt they cannot kill him if they record his interview or maybe they’ll arrest him and send this video clip to the media saying that they are not as barbaric as people are portraying.

“At this point I was still sure that Gaddafi forces have got me. After the interview, he said, ‘Do you have any idea what you have survived?’ As he was talking, I saw a man climbed up on the mosque and flew a rebel flag from its minaret. I was like, Oh My God! They are rebels and I am actually saved,” he said.

He saw two rebels walking towards him whom he had seen many a times before on the frontline. They hugged him and apparently recognized him. “I felt completely different now, I was a free man again,” he sighed.

The commander he was talking to was a Libyan banker, who had joined the fight like other civilian. “He said they had heard about four missing journalists and assumed I was one of them. He said whole world is looking for you and every newspaper has your photograph and news. This made me so nervous and anxious because I knew if my family knew about this, they would be devastated. I badly wanted to inform my colleagues of my wellbeing because I believed they too would be extremely worried,” he said.

Finally, five of them — rebel commander, his three men and Qadri left in the pickup for Benghazi.

At about 8.30 pm, they reached hotel Uzu, where the AP crew was waiting for him in the compound. All hugged each other and Ben handed him Thuriya satellite phone to speak to his family.

“As I called, my wife answered the phone with a sobbing tone and started crying as she heard my voice. By then, she had already been informed about my safe return. I felt so bad to make my family go through all that agony and pain,” he said.

Altaf Qadri meets his friends and colleagues after his return.

“I appreciate the way Associated Press handled the whole thing. They made sure that my family is taken care of during those long terrible hours of agony. My long-time friend and colleague Rafiq Maqbool, who is based in Mumbai, flew to Amritsar to be with my family. My eldest sister and her husband were also advised to fly to Amritsar from New Delhi. May be they were expecting something worse. I had to cut short my assignment to back with my family. If it was not for my family I would have stayed back and covered it till I was supposed to cover it,” he said.

Qadri, 35, won a World Press Photo award for his poignant photograph of relatives mourning over the body of a man killed in a shooting by police in Kashmir. In 2003, he joined the European Press Photo Agency and covered the conflict in Kashmir. In 2008, he began working for The Associated Press in the Indian city of Amritsar. His work has appeared in magazines and newspapers around the world and has been exhibited in the United States, China and France.