By Yogesh Maitreya,

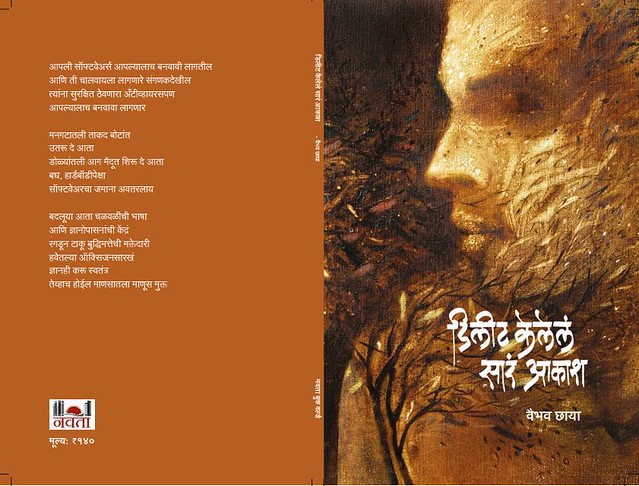

“With all my baggage gone I can travel light now, forging on deeper into forest” says Haruki Murakami in his Kafka on the Shore. The same feeling can be drawn as soon as one finishes reading ‘Delete Kelela Sarr Aakash’ (Entire deleted sky), the first poetry book by Vaibhav Chhaya. Vaibhav writes poetry in Marathi. And the forest of his poem is equally risky and beautiful, one who could see the life in the underbelly, would certainly remain unsettled after brooding into the forest of his poems.

The book is the another milestone in the tradition of dissent literature, politically known as Dalit Literature, though Vaibhav himself is not comfortable with the use of nomenclature of Dalits. He argues “how can we be Dalits when we assert and speak for our rights”. Whether we call it Dalit literature or not, his poetry sets new grounds of aesthetic so much so that it establishes new debate that not only speaks about the broken people (Dalits) but deals with many contours of humanness and assertions for human-rights with use of crude metaphors and unusual imaginary. The book is politically charged and that makes him a maverick voice in contemporary debate of poetry. For instance in memory of unfortunate situations of textile-mills in Bombay, he says, into the debris of crushed textile-mills/ polished malls are there/ into the sweet-sleep. The assertion against injustice and aesthetics go hand in hand in his poetry. And with him, the poetry awakens into the domain of night.

Vaibhav Chhaya

It was one such night, when I met him.

Vaibhav Chhaya is only two meetings old to me. Having been familiar with his Facebook profile for a long time, I could hardly keep myself settled after reading his poetry on his profile-wall. I was unable to trace what illuminates his poetry, what lies in the underbellies of his maverick metaphors until during one random evening he arrived and began conversing, with his curious tales of the outside world and people, as if I knew him for a long time. The feeling of knowing him for long at the first meeting was the first vivid impression I have acquired. But Vaibhav was obviously a grander mystery to me.. Penetrating the world of his poetic sensibilities, it is quite uncertain to predict about the aesthetic elements that shape his poems to the level of the third-world . The third world that is beyond the notion of ‘good’ and ‘bad’, the third world which magnifies his personality both clear and ambiguous as he goes on to say in one of his poems called ‘Identity Crisis’:

My identity is really

A perplexing thing,

Or it might be a mask

That someone has put over me

As if a wound drenched in blood

Or an artificial tree of plastic

Like previous poems which have been written on ‘identity’, he makes an honest attempt here to show the ambiguity within his own self, and takes readers to the route of clarity thereby tracing the precise roots behind the genesis of his kind of poems. The verses above also demarcate the judgmental imaginations of readers towards the poet’s personality. At first, he accepts the perplexity within him, yet he dares to trace the origination of it in outside world as he says referring to his identity:

it might be a mask

that someone has put over me.

Further he uses the brutal metaphor, when he juxtaposes his identity with, a wound drenched in blood, and startles readers with comparing identity with the lifeless, an artificial tree of plastic.

Vaibhav, being a poet associated with the Ambedkarite movement for long, a witness of caste-atrocities like Ramabai Nagar that took place in 1997 in Mumbai, seems to develop an ameliorative consciousness about caste and its brutal practice, as in one of his short poems from the book, he declares his stand on caste and the world in which it functions.. In his poem ‘deliberately running far’ he says:

deliberately running far

long from the illuminative lightings

I am not scared of my shadow

that keeps me along with her

to my each footprints

but to this light

has kept the ghost of caste, sex and race behind me

particles by particles into the dark

we must accommodate ourselves

to be born newly

with pellucid bodies

then there won’t remain

the colour of my skin

my underlined virility

and follower, that is my caste.

With the above poem, Vaibhav tries to transcend the meaning associated with the idea of light, especially into the poetic world, perhaps because of his associations with different levels of lives channelling through his friends who make their lives in slums, or Hijraswith whom he can easily establish humane relationships. All such lives, somewhere illuminates their real existence as well as be prone to all possible humiliation by ‘conventional society’ in the empire of darkness. Perhaps being with this darkness closely, he labels ‘light’ not as a hopeful time of the day but something that observes and keeps alive the practice of caste and humiliation with its open eyes. But what exactly he meant by getting ‘accommodate into the dark’ produces unpredictable interpretations. Nowhere in the poetic sensibilities ‘the darkness’ has been used for the rising of any kind, but Vaibhav dares to do that, perhaps because of the safe-shelter he imagines that not only dissolves but accommodates his footprints those mark the impression of his caste .

His use of metaphor is merciless and it pulls the attention of readers, unsettles them. In another poem called ‘Enclosed in file’ he writes:

into the black bag, friction with dog’s tongue

their half-torn foetus

ghostly bodies

uprooted shoulders

torn joints

much of these would be enclosed in a file

into the FIRs of police records

these should be searched anew.

In much of contemporary poetry on Indian soil, the tumultuous use of metaphor to show apathy of Indian society and their crumbling sense of emotions could not be identified, in short, the contemporary Indian poetry could be universal at virtual parlance but not at all provincial. Vaibhav with his first book of poetry works like a painter, with brutal colours of experiences in his hand and attempting to paint the honest painting of Indian society while depicting foeticide, naked parades of Dalits women; atrocities of Dalits, their rapes. He captured all these into phrases maintain the element of aesthetic of broken people. The humiliation of Dalits at every corner in contemporary Indian society being an everyday scene. And since the Dalit panther movement, not much heed has-been given to these events in the ambit of literary aesthetics, though many attempts have been taken place via various magazines and pamphlets and by various means of circulation of literary pieces, especially in the tradition of literature of dissent. But in the poetic tradition,Vaibhav’s attempt to project the apathy, crisis of aesthetic-struggle of Indian society and their negligence towards Dalits atrocities as well as lives of all the oppressed groups, is not only a fresh attempt but it also goes on to establish the transformed aesthetic sensibilities of the world which have never been taken seriously by larger/mainstream Indian forces.

To common readers, the words, phrases or metaphors he used might amaze and shock as Hjirha (eunuchs), prostitute, dog, rape, foetus etc. are the commonly used words without which the world of his experience and his sensibilities those telecast the gruesome risk at which his people live would be incomplete. Thus he might be seen as the offensive poet to many. But before letting any thought to be the notion of his personality, readers must penetrate deeply and cautiously to understand the world behind his poetry.

His personal world in his poetry is a seldom event, but when it comes, it breaks the notions the way one would have looked at the subject matter. In one of his poem named ‘Mother’ he writes:

nurturing a foetus is not easy

as if keeping pets like dogs and cats

more difficult than this

is to bear abortion.

Vaibhav is the ninth child of his mother. The previous eight did not survive. If his metaphors are brutal and merciless,his compassion when he digs into pain of his mother is impeccable. It is at his level, he develops an authenticity to look beyond the notion of sex or gender. He seems to observe affairs on a humane-level, as he further writes:

while transforming woman into mother

she combs her intestines

destroys it

makes that place neat and clean

for habitation of child.

The above stanza projects almost an ontological imagination with its power to think again on the way one could look at the motherhood. But it is the power of poetry that despite have been written without any particular form, meter, and flow marks the impressive mark on readers’ mind.

The poetry book, has been written in Marathi is not at all Dalit rhetoric as some half-minded critics and literary personalities define in the past. The book marks a different place for itself as it not only unsettles the readers by its ontological imaginative power, it also brought their attention back to the subjects to which we look down as outdated matters. For the readers of poetry in Marathi, ‘Delete kelel sarr aakash’ is a fresh and welcome read. The book must be read by all those who want to read the meaningful literature.