In the first part of a three-part series on the missing people of Jammu and Kashmir, Raqib Hameed Naik looks at the courageous work of Parveena Ahangar, the woman who started the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons.

Srinagar: Over the past 25 years, Pratap Park, an area near Lal Chowk in the heart of Srinagar, has witnessed numerous protests, thousands of tear gas shells, pellets and bullets fired, and hundreds injured. On the 10th of every month, however, a group of people, mostly women, gather and protest quietly with posters, photographs and small write-ups on family members who have gone missing in the state over the past two decades. In Kashmir, also known as the ‘Valley of Saints’, Pratap Park is a reminder of what the state has endured; it also reminds us that despite the pain shared by thousands, they continue to fight for justice in the world’s most militarised zone.

The protestors congregate under the banner of Associations of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), an organisation which was started by Parveena Ahangar, a mother whose 16-year-son was picked up by security forces in 1990. Her son has been missing since. It is a fairly common story in the state; a story that brings together hundreds of families who wish to know where their children went, what happened to them. But for these people, reliable information is scant, state government’s assistance nearly zero, and hope, their only weapon.

As militancy flared up in valley after the rigged elections of 1987, the region witnessed a barbarous clampdown by government forces on the people of Kashmir, with many picked up deliberately mere on suspicion who never came back.

The disappearance of large numbers of persons is termed ‘enforced disappearance’ by the United Nations Declaration on the subject. According to estimates, there are around 8,000 to 10,000 cases of involuntary and enforced disappearances in Kashmir, mainly attributed to the work of Indian security establishments since the onset of militancy.

Although on the surface, the national media portrays pictures of normalcy and peace returning to Kashmir, an important question remains: where did 10,000 people or 0.0008% of J&K population (considering 2011 census) vanished?

In 1994, it was this question which led Parveena Ahangar, often termed as ‘Iron Lady of Kashmir’, to set up APDP. It was her attempt to bring together families of disappeared persons from different parts of Jammu and Kashmir. The pain had to be shared, if one had to fight it.

Parveena, 56, was born in Srinagar and got married at the age of 12. Despite not receiving any formal education, she has brought global attention to the issue of forced and involuntary disappearance in Kashmir. Her efforts have ensured that the cause hogs international attention. She has represented the cases of disappearances on various international platforms by travelling to Philippines in 2000, Thailand in 2003, Indonesia in 2005, Chiang Mai in 2006, Geneva in 2008, Cambodia in 2009 and most recently to London in 2014.

On the 10th of every month, the family of missing persons, headed by Parveena, seek answers and justice from both the state and central governments on the whereabouts of their loved ones. Not that much happens as a result of this, since the state government does not even acknowledge that such a huge number of people have gone missing in the state.

The APDP office, located in Hyderpora, Srinagar, has always been a sacred space for victim families who share and grieve their pain together. Since the last decade, the office has also been providing medicines, clothes and other essential things (purchased from donations) to the deserving victim families, who have lost their lone bread earners.

As the hour needle of the clock ticks to 10 in the morning, the APDP office space starts to fill with family members of victims coming from Srinagar to far-flung villages of Kupwara District to collect their monthly stock of medicines and other essentials.

Praveena, sitting on a chair in the corner of room welcomes the women coming in with a warm hug. “We all have a similar pain. Some among us lost their sons, some lost their fathers and others lost their husbands,” she says.

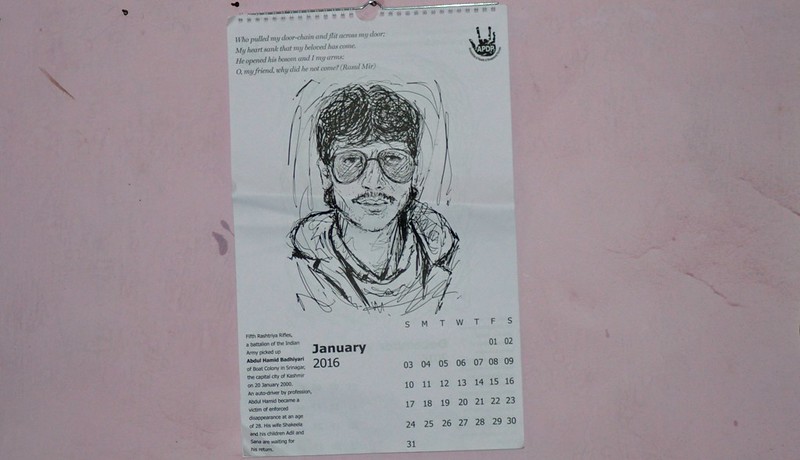

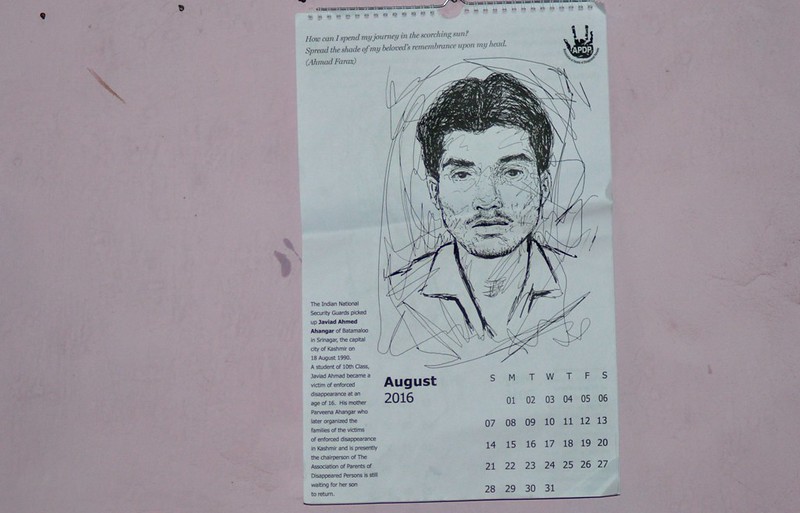

A Calendar, where each month denotes one missing person

As I sit in the ADPD office, a 2016 calendar hung on the opposite wall catches my attention. This is no ordinary calendar: there is no art, no scenery, and no models promoting a cosmetic product. On the contrary, the month of January in the calendar contains a sketch of disappeared person, a quote of a poet and a little brief about his disappearance.

The brief reads: “Fifth Rashtriya Rifles, a battalion of Indian Army picked up Abdul Hamid Badhiyari of Boat Colony in Srinagar, the capital city of Kashmir on 20 January 2000. An Auto-driver by profession, Abdul Hamid became a victim of enforced disappearance at an age of 28. His wife Shakeela and his children Adil and Sana are waiting for his return.”

On the novel idea of printing calendars with 12 enforced disappeared persons dominating the 12 months of a year, Parveena says, “We came up with this idea so that everyone comes to how Kashmiri’s were forcefully disappeared by Indian security forces. It is a message by families of missing persons to the government as who is behind the disappearances of their loved ones.If they are alive unite them with us or if they are dead show us their graves.”

She adds, “We will continue to the print the calendar every year.’’

Parveena would know this calendar much too well.

The month of August in the calendar has the sketch of one 16-year-old youth, Javaid Ahmed Ahangar, her son, who was picked up by security forces from his relatives place in dead of the night on 18th August 1990.

Before APDP, a fight in vain to find her son

“My son was 16 and had just passed his tenth standard exams,” recounts Parveena. “That fateful night on August 18 1990, he had gone to his cousin’s place to study. A search for a militant named Javed Ahmed Bhat was going in our locality that night. The forces entered in the wrong house which belonged to our relatives where my son had gone to study, the forces shouted ‘Javaid’, as my son name was also similar to the name of alleged militant except the surname Ahangar, my terrified son scaled the wall out of fear where he was caught up by the forces and taken away to some unknown location.”

Parveena was unaware about his son being picked up until a lady from her neighborhood came knocking at their door at 3 am in the morning. “My husband opened the door. I was inside another room where I overheard the conversation that my son ‘Famba’ (nick name of Javaid) has been picked up by Indian security forces. I left my house barefooted and other women of the locality also followed me as we took out a procession to local police station and then to police control room Srinagar to force officials to release my son.”

In those painful and hard days, Parveena says she used to assure herself that her son Javaid will be let off because he wasn’t a militant. But unfortunately, days turned into months and there was no word about her son. Even as she continued her crusade by organising protests at regular intervals, a day came when the Superintendent of Police Control Room, Bashir Dar told her that her son was recovering from his injuries in Army owned BB cantt hospital in Srinagar.

“I along with other Police officials went there to get my son but unfortunately it turned out to be a hoax as I could not trace him there. I visited the same hospital twice again, believing that may be this time I could find him, but as usual came back empty handed,” says Parveena.

After months of wait, fed up with police officials lies, Parveena along with the family of Basharat Shah, an M.Com student, who was also picked by security forces from Sopore in Baramulla District, took out a huge procession of protesters to Police Control Room Srinagar where the then SP was quoted by Parveena as saying, ‘Go and file a case in court’.

So, she moved to court in Srinagar in 1991 which lead to an inquiry in the case. “It was proved that three Army officers had picked up my son,” tells Parveena.

In the later years, she visited several jails and torture centres across J&K to locate her lost son but every time, the harsh reality left her cold. “He isn’t here,” was the most common response. Finally, in 1994 she formed APDP by identifying and gathering together the families with similar stories from across the Kashmir whose kin’s were subjected to forceful disappearance

She fought her case legally till 1997 and the case file was sent to Union Home Ministry for sanction to prosecute the accused Army officers. This was of course, never granted to the state. “I had never missed a single hearing during those seven years. I used to leave in the morning and come back in the evening. Numerous times, I along with other victim families organized protests outsides the gates of high court and lower courts.”

As Parveena continues to recount her ordeal, she talks of one incident in particular. “During the proceedings, one of the accused, an Army colonel, came to me and said: ‘Behan, kya chahiye tumhe? Kitna paisa chahiye?’” (Sister, what do you need? How much money do you need?)

I only replied, “Muje kuch nahi chahiye, Muje mera beta chahiye “(I don’t need anything, I need my son.)”

Parveena’s legal fight for justice has left her dejected as she says, “I have lost faith in judicial system.”

The early years and the next generation’s fight

In 1994, Parveena formed the APDP, to help her fight along with the families of other disappeared people. “For 5-6 years after 1994, all the victims used to meet twice: on 15th and 30th of every month at my home where we used to discuss our next course of actions.”

Then, says Parveena, a victim suggested that we start meeting at public places so that people also become familiar about their demands, pain and this suggestion was readily accepted by her after which the victim families starting meeting and organising silent sit-in protests in Partap Park.

“Since last 15 years, we have been organising a sit on the 10th every month, seeking information, accountability and justice from the Indian Security establishments who are responsible for the disappearance of our family members.”

Since its inception, APDP has mobilised a large number of students, activists and professionals from different parts of world who through the association have been able to engage on issues of justice, reparation, impunity and legal course besides advocating the harsh struggle of the victim families.

In 2005, Parveena was nominated for Nobel Peace Prize for her strength and human rights activism. Later, Indian media Channel CNN IBN nominated her for an award, which she rejected on account of the way the pain and tragedies of Kashmiris have been depicted by the Indian media.

For Parveena, mainstream Indian media has always been indifferent when it comes to covering the lives of the common people in conflict-ridden Kashmir. Recounting her experience while she was interviewed by a Delhi based journalist, she says, “We were on a monthly sit in when a reporter working for a Delhi-based newspaper came to me and asked how many families were presently here in the protest. I replied around 300.He went on to write in his report published in the newspaper, by misquoting my words that there are only 300 cases of disappearance in Kashmir.”

Two decades after its formation, APDP now is more organised as Parveena’s daughter Saima Ahangar joined her mother’s fight by taking over the paper work of the association after finishing her senior secondary school. A research on the exact number of disappeared persons is also underway. “APDP have already met around 5,000-6,000 cases of enforced disappearances and our rough estimates say that the cases are around 8000-1000,” says Saima.

An estimate issued by the J&K government in 2009 confirmed 3,429 cases as missing between 1990 and 1999 whereas no tally existed after 1999.Parveen outrightly dismisses these calculations. “The State government has always been good at hiding,” she says.

The courage of Parveena and thousands of families seems endless, even as they continue their struggle to seek answers from the government. Are their loved ones dead or alive? “This is our fight for Justice,” says Parveena, defiantly. “It will only end when rays of justice will pierce through the sky of Kashmir.”Part II– 3