Different shades of grey: A review of The Plague Upon Us

By Ashaq Hussain Parray

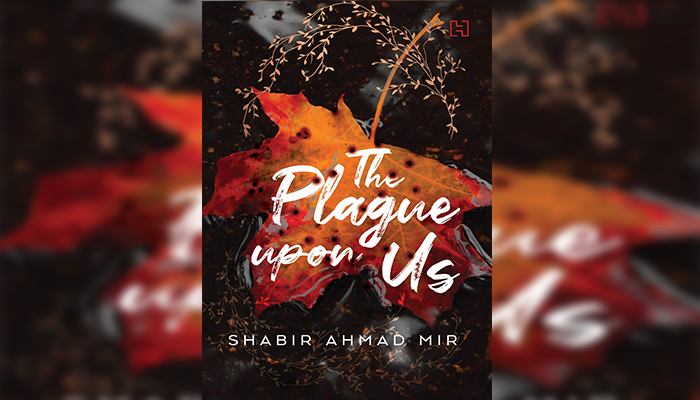

Shabir Ahmed Mir’s debut novel The Plague Upon Us (2020) is a bold new voice of a storyteller from Kashmir. Living up to its name, the novel lays bare through intricate realistic detail the literal as well as the metaphorical plague that has descended on Kashmir.

Mir opens the novel with an epigraph from the well-known Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex and narrates four inter-twining tales surrounding four characters from across the social and political fabric of Kashmir. Initially, one wonders why Mir chooses to open a novel set in Kashmir and about Kashmir with an excerpt from a Greek tragedy. However, as we course through the pages, we learn that Oubaid, formerly a member of the Brotherhood (Ikhwan) used and abused by Major Gurpal who is a representative of the Indian security apparatus for counter-insurgency operations, acts as an Oedipus like figure as he watches the plague of blindness unfold the place around him. Mir by referring to a Greek tragedy seems to be hinting at viewing Kashmir as a Greek tragedy where the story has already started before a character is born and continues when s/he dies or exits the stage. As much as we ask in Oedipus a question like who is responsible for the plague on the Thebans and who is responsible for the Oedipus’s fate, Mir leaves us wondering about who brought the plague upon us while showing us various facets of conflict and its people─ militants, renegades, common masses, police and the security forces─ all torn apart by their hobbyhorses. This is a fundamental question to which he does not have a readymade answer. In a place like Kashmir where the lines are neatly demarcated that either you are with the people or against the people, Mir braves to explore the in-between territory that falls between officially sanctioned social and political labels of being a militant, renegade and a soldier.

Like a host of other fictional works on Kashmir, Mir explores post nineties Kashmir and delves into the possibilities of exploring beyond the officially sanctioned role of people when viewed through identitarian politics and other ideological markers. Often a person trying to write about his/her past tends to be romantic or idealistic as s/he is overtaken by the nostalgic vein. However, Mir resists this approach to past like Chinua Achebe and does not end up with valorising the Kashmiri armed fighters, the security forces and the common masses – he shows people from all walks of life susceptible to the same human foibles. Mir tells us that militants “would come in the middle of the night, knock gently, eat desperately, sleep uneasily and leave before dawn” and once a militant or any association with them, “you are marked for life.” Mir does not judge. He does not take any ideological position vis-à-vis any character. He has learnt the art of delving into a character very well.

One of the striking aspects of the novel is its psychological insight into the motivations of characters. Major Gurpal is tired of working at a hostile place like Kashmir but still chooses to build networks with the local people for timber trade and using them against each other. Oubaid wills to interrogate a Zaeldar (a rich landlord) scion to extort money but has drowned headlong in Jozy’s love. Muzaffar is a rebel who is capable of thinking – he knows well what Major is up to and at the same time trusts and distrusts Oubaid, his only link to the enemies. Hamid Puj’s only dream is to get rid of the caste that sticks to him like a burr and become Abdul Hamid. However, things don’t come easily at a place marked by asymmetrical social and political relations. The result is that people fall “like leaves on the bridge, and off it. Hit. Injured. Crying. Running. Bleeding. Falling. Dying. Pretending to be dead.”

Mir explores the Kantian idea of using and abusing a fellow human being for a mean purpose. Oubaid is forced by circumstances to either join the Tehreek and get killed by Major Gurpal or join the Brotherhood and be hounded by the militants. In between the devil and the deep fire, he chooses to play with both that eventually lands him into darkness. “So Oubaid was to be a two-headed dog, running between Muzzafar and the Major and for both of them. Did he have a choice, he wondered. He looked at Major Gurpal and considered his position. No, he didn’t.”

Oubaid’s only purpose in life is to survive by hook or crook as he tells Muzaffar, his militant friend, “I was trying to save myself. To survive. That is all I have been doing since I was born – trying to survive. I never wanted anything else.” Survival becomes an important theme early on in the novel. Oubaid’s fate forces us to ask some fundamental questions on the nature of living and surviving. Mir is perhaps trying to hint that reduced to bare bones, a human being’s primary instinct is to survive.

Mir builds a non-linear and non-cohesive frame narrative often marked by repetitions. With realistic prose punctuated by at times flashes of poetic brilliance, these repetitions are deliberate to reinforce the idea of the all-pervasiveness of the hellhole called conflict and the replication of the human lives in a theatrical manner.

In the beginning, Oubaid is plagued by voice(s) in his head that exhort him to remember what happened in the past. Adamant and too frightened at first to visit his past, he has to keep the King busy by telling him stories and to get rid of those voices. In a fashion that obviously alludes to the Arabian romance One Thousand and One Nights, Mir kick-starts his novel revealing four interlinked stories through Oubaid’s memories. We learn early on that storytelling and the idea of time as always running reminiscent of Eliot’s “Hurry up please its time” emerge as major tropes that open and close the novel. Within a period of one thousand minutes and one, Mir tells us four tales almost beginning in a fairy-tale trope of “once upon a time” quickly undercutting it by foregrounding violence and keeping the reader on tenterhooks.

Exploring themes like love, loss, desire, hope, friendship, betrayal, identity, courage, caste, power, violence, memory and colonial enterprise Mir through his brilliant portrayal of the lives of his characters that come from various social categories explores what it means to live in a conflict zone. The novel makes marvellous use of colour imagery especially with the shades of black and red. Colour symbolism like Black and Red, marked by the repetition of words, alliteration, allegory and short sentences reinforce all-pervasiveness of the plague.

At times, it seems almost Orwellian in the way people in the novel are just made to disappear or reduced to nothingness. Surveillance in the form of human cameras like informers and collaborators is present throughout the novel. Dehumanisation is a major theme that runs through the novel. One can see women getting dishonoured and people like Altaf Firdousi playing foul in deceiving his own people into forming an independent party while also working with Major Gurpal Singh. Beginning as a poet, he decides that “if he could no longer sell heartbreak, then he would sell patriotism.” The dehumanisation of actors and the acted comes out in nude reality in the torture chamber of TALK1, “the cesspool into which all the surrounding camps dumped their sewage of detainees.” However, the novelist does not condemn these people into neat and clean categories. Always cussing and shrewd Major Gurpal Singh loves Russian literature and says “I wish we could fight our wars like they did in the old times. Fight during the day and sleeping peacefully at night… You could even drink with your enemies once you were done with the killing. There is nothing of that now… No honour… It’s a disgrace.” On the other hand, a young Muzaffar learns at Ashfaq’s residence the truth about militants, “Contrary to his expectations, they did not talk about strategies, ambushes, attacks and escapades, but joked and quipped about ordinary things, like a recent cricket match between the arch-rivals in the subcontinent, their old maths teacher of whom they were still afraid, how they craved for a decent bath while hiding somewhere in the mountains or missed a hot cup of nun-chai on cold mornings.”

Surprisingly though, Mir does not tell us more about his women characters like Sabia, Jozy and Maimoona except some details that fit into his scheme of things. There are no women rebels or informers, and it seems as if women are too passive to play any role beyond their scripted existence. This should have been given more space because the novel chooses to deal with our history punctuated by violence but sadly in this gory battle, women get reduced to mere whims of men which however is not the case at all in the context of Kashmir.

Moreover, Mir does not deal extensively with the Pandit displacement save a page or two. However, the novel goes way beyond some established narratives on post-1990s Kashmir often marred by polarization and brilliantly explores the forbidden territories of human desire because “the truth is perhaps the only justice we can have; the only vengeance we can wreak.”

Ashaq Hussain Parray is a researcher at the department of English, Aligarh Muslim University.