Samvartha ‘Sahil’, TwoCircles.net

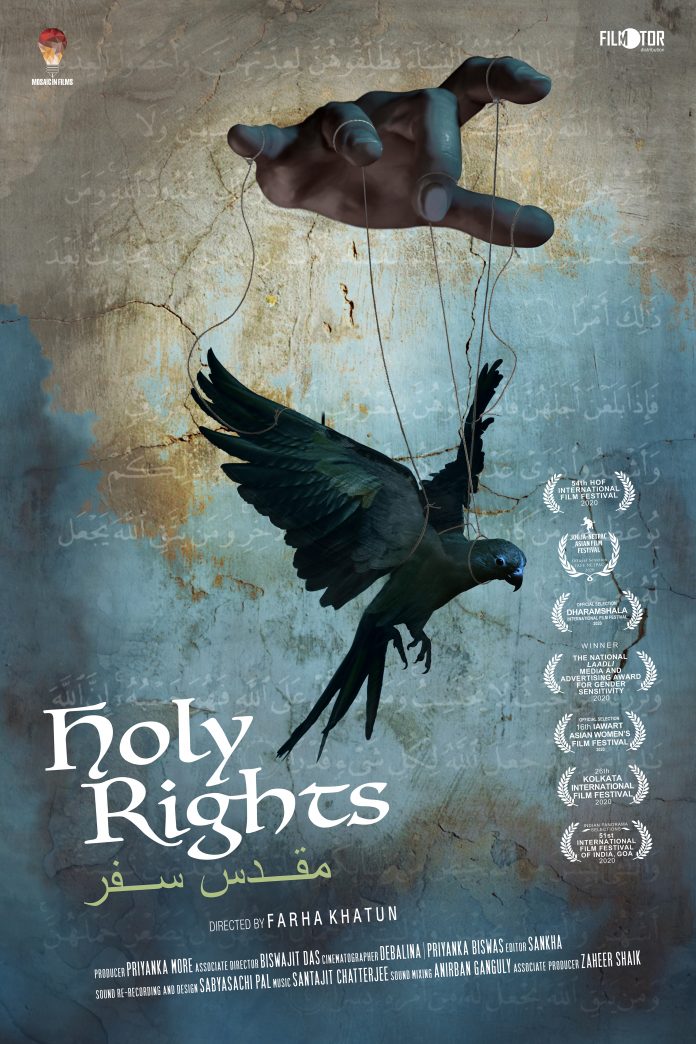

Shot and edited between 2016 and 2019, at a time when Hindu fundamentalism in India has tightened its grip on state apparatuses and Islamophobia has evenly spread across the society, Holy Rights by Farha Khatun contextualizes the incredibly complex battle for gender rights by Muslim women.

While the entire Muslim community is under threat, a parallel battle for gender justice and gender equality by Muslim women could turn counterintuitive to their original vision and politics. By capturing and chronicling the complexities of this multiple and parallel battles, without diluting the central vision of gender justice, or forgetting the overarching Islamophobia, Holy Rights emerges as one of the strongest and also one of the most courageous films to be made in current times.

Holy Rights follows Safia Akhtar, a resident of Bhopal, who is one of the first women to become a Qazi (Muslim Clerics, traditionally male, whose verdict is final on issues related to Muslim personal law), in India. She was also at the forefront of the fight to ban instant triple talaq.

Lost in Interpretation

Very early on in the film, we see few women confiding in Safia their personal stories of divorce by instant triple talaq. One woman speaks about how she got separated from her husband after he uttered talaq thrice over the phone. Another lady narrates the humiliating experience of being divorced by her husband on a busy street, followed by the strangers, who had gathered, loudly declaring that the marriage is over now.

To these women, Safia explains what the guidelines for talaq as per Quran are and asks how the male Qazis can overrule the words of Allah and sanction validity to instant triple talaq?

Here we realize not just that the Qazis have misinterpreted or rather mister-interpreted the Quran through their gendered gaze, but also realize it is such occurrences which prompted Safia to undergo the necessary training (along with 30 other women) to become a Qazi.

Safia and her comrades went on to challenge the men within the community, who importantly are male religious heads, and also engaged in a bold battle to demand ban of the non-Quranic and non-Islamic triple talaq, by moving to the Supreme Court and writing to the Government.

Layered and entangled complexities

Right in the middle of the 53-minute long film, there is a defining sequence that reveals the complexities of the matter and also the politics of the film.

This is how the sequence flows:

A religious Safia while about to perform namaaz (prayer), asks the filmmaker, a non-practising Muslim, whether she offers namaaz every day. On hearing the answer in the negative, Safia in a seemingly disappointed tone tells the filmmaker, “galat baat,” (It is wrong) and without stopping there, she repeats, “bahut galat hai” (It is very much wrong) and suggests Farha to take time out of her busy schedule and pray every day.

Cut to…

Safia speaks about a news/rumour in circulation about a Fatwa to be issued expelling her from Islam. Responding to this she asks in an unshaken firm voice, “Who are they to expel anyone from Islam?” Declaring her faith a personal matter between her and “my Allah”, and that she is only following the Quran’s path, Safia announces, “Merely their saying or issuing Fatwa will make no difference. I am Muslim, I love Allah, I fear Allah, and I am following Allah’s path. So I am Muslim.”

Cut to…

Taajul Masjid, Bhopal. An all-woman meeting is held under the banner of Bharateeya Muslim Mahila Andolan. The organizers of the meeting ask the gathered women to introduce themselves and insist they be loud enough to be audible to everyone in the assembly. “We also want you to get rid of your inhibitions, your shyness so that we have the strength to speak to people,” explains Safia. Housewives, girls who dropped out of education after high-school – all introduce themselves. Spelling out the purpose of such an organization and such meetings, which is “to gain knowledge about everything”, Safia reassures them that it is a safe space and the ladies, “should be able to discuss frankly”. As the meeting progresses, she tells the gathering, “The biggest issue with Quran is that it is written in Arabic…”

The spoken words continue but the shot cuts and shifts to an interview Safia is giving to India TV, where she continues with the same sentence…

“… Because of that nobody understands the meaning.” Then she goes on to explain what problems this gives rise to. Whenever women have any problem concerning their marriage, talaq, or property, Safia says, they go to the Qazi or Mufti who are considered the ultimate authority on Islam and are believed to be right, even when they are wrong.

Safiya then elaborates on the struggle she and her comrades of concern are battling: “So we make women aware, and tell what rights they have in Islam. Our Quran speaks of equality, justice, mercy, and wisdom. So our Constitution and our Quran both have the same values. So we want that our law is made as per the Quran. So it is obvious that the country in which we are living and its Parliament will pass that bill. So we have given a letter to the Prime Minister that the draft on this matter should be considered and that our laws should also be codified and we should get the same benefits that our religion provides us.”

Cut to…

Safia and her husband Syed Jalil Akhtar are watching TV while having dinner. They are watching Ravish Kumar’s Prime Time where he speaks on how cow smuggling is being used as a justification for lynching and criminalizing people from the Muslim community. With statistics about lynching and criminalization of Muslims, Ravish Kumar speaks about how after 2014 there has been a rise in Islamophobia and communal violence against Muslims.

This sequence which comes at the centre of the film captures the heart of the struggle of both Safia and the filmmaker. It also brings forth the levels and layers of the battles being fought.

Appropriation and expulsion

At a time in history, when a communal and a fascist regime has declared war against an entire religious community, fighting a parallel battle that locks horns with the people within the community is certainly not easy. It does not just run the risk of the battle being appropriated by the larger political enemy but also of being antagonized within, if not out-casted from the community.

When this battle for the ban of instant triple talaq began, we see in Holy Rights, how certain media houses that have a communal gaze, enthusiastically amplified the voice of Safia. We also see how the gendered gaze of the interpreters of the Quran and their allies found Safia to be a traitor and wanted to expel her from Islam.

The vulnerable section within the community become more vulnerable by the very support they receive. But the women risked the vulnerability of being weaponized by the state and fought for a liberatory political demand.

Fight against power and not for power

When we hear Safia say, “Who are they to expel anyone from Islam,” while responding to the news/rumour about a Fatwa, we realize the depth of Safia’s politics. Even in a moment when she has become the individual target, her question is not “Who are they to expel me?” but “Who are they to expel anyone from Islam?” It is not the kind of privileged feminism that bell hooks warns us against, where the battle is for a share in the power. It is a kind of feminism that bell hooks propagate – a feminist politics driven by a love-ethic formed on the idea of love, justice, and equality. For Safia, the struggle is not just to occupy the male-dominated space of religious leadership, but to liberate the community from the hegemony of patriarchy and its interpretation of the Quran, which is wronging its women.

The larger battle

The film Holy Rights, while documenting this struggle and also participating in this struggle, doesn’t forget the larger battle the community is fighting against communalism and Islamophobia. Though not unaffected completely by the current socio-political scenario, we don’t see (at least in the film) Safia engaging much with it. But the filmmaker has consciously chosen to engage with it by highlighting the issues of lynching, criminalization of Muslims and the violence against them.

To counter the popular narrative about Muslims lacking love for the country, the filmmaker underlines the patriotism among these women by showing them singing “jis desh mein Ganga behati hai” and putting up a play which speaks of Constitution with great respect. We see through this filmed play, how these women locate the rights of Muslim women within the Constitutional values. We see how the women identify themselves as rightful citizens of the country which, at least in its Constitution, guarantees them liberty, equality and justice.

The necessary battle

While engaging in a parallel battle against the male dominance in religious leadership and the wronging of women in the community, Safia and her comrades of concern, also realize the importance of another battle at an individual level among the womenfolk within the community. And they engage in it too. They not only make the women folk aware of their rights as per the Quran and the Constitution but also assist them in finding their voice and strengthening their voices.

Exploring complexities and resisting stereotyping

While showcasing these struggles, which like vortex go deep and turn more intense as one goes deeper, the filmmaker problematizes the struggle and also resists stereotyping at the same time in two extremely significant moments in the film.

At the All India Muslim Personal Law Board Conference held in Kolkata, where the men on stage are speaking about the protection of women’s rights and upholding the Shariah law, the filmmaker moves to the corner where women are seated and puts the mic before them. While some young women initially speak to the filmmaker and critique the Govt’s intention to ban instant triple talaq and defending the custom of instant triple talaq, other women around them first request and then instruct the filmmaker to leave them alone. Some tension is built between the filmmaker and the women gathered on the side-lines of the conference. When the filmmaker tries spelling out that there is a difference between listening to men and women about issues concerning women, a burqa-clad young lady tells the filmmaker in clear English, “Whatever you wish to know is being spoken by the men on stage. Just listen to them and let us also listen.” The filmmaker is then immediately asked to leave the “segregated place”.

While on one hand, this moment shows what Safia at the beginning of the film says about women viewing themselves “through the eyes of the men,” the same moment also punctures the majoritarian and stereotypical view of Muslim women as being submissive and uneducated.

The woman, who initially narrates her experience of getting separated from her husband after he uttered talaq thrice over the phone, is seen in one of the end sequences of the film coming to Qazi Safia with her husband and seeking intervention. Safia explains to the husband that as per Quran instant triple talaq is not valid. The lady’s husband disagrees with Safia and, in a desperate, restless, and slightly vulnerable tone, says, “As it is I have committed a sin by giving talaq. Now I can’t commit another sin by staying with her.” He repeatedly says he cannot agree with Safia’s (miss)-interpretation of the Quran and cannot accept his wife back because he has to “face Islam, face Allah” and that he “cannot go against Islam.”

The words of the husband reveal how deeply the interpretation of the male Qazis and Muftis about the custom of instant triple talaq has been etched in the minds of the members of the community, and how difficult it is for anyone to change it, even though the change is in accordance with the sayings of Quran. At the same time, it also shows how the man who somewhat regrets his decision and action of instant triple talaq (“As it is I have committed a sin by giving a talaq”), now doesn’t want to reunite with his wife, because he subscribes to the interpretation of the Quran by the Qazis. The husband, who otherwise would have reunited with his wife, now sticks to his decision, and goes against his heart because he wants to “face Islam”.

The film exposes how an inhumane custom, which largely harms women, also traps men and with the slight glimpse of the man’s vulnerability and complexity, also punctures the majoritarian and stereotypical view of men and specifically Muslim men.

This aspect is underlined thickly by introducing Safia’s husband Syed Jalil Akhtar, a very tender and supportive partner to Safia.

Safe spaces: making the politics personal

By showing the loving relationship between Safia and Jalil, which undoubtedly adds to the strength of Safia, the film brings forth an argument for the need for safe and loving spaces at a personal level and how it is an essential part of and for politics.

The confession of Jalil Akhtar saying earlier he wasn’t the way he is now, makes one wonder if it is Safia who turned him into what he is or is it the love-bond between them which enabled him to become what he has eventually become. What gets communicated is the strength of love to humanize us and create safe spaces, and also the necessity of safe and loving spaces for us to humanize ourselves and gain strength as individuals.

The necessity to create safe and loving places gets highlighted throughout the film. We see how Safia and her comrades of concern create a safe and loving space for women to meet, bond, share, and organize. We see how this safe and loving space not just enables these women socially and politically, but also by creating an atmosphere for them to let their guard loose, makes it possible for them to express themselves (seen through dancing, singing, and merrymaking) and just be themselves unhesitatingly.

By highlighting this creation of safe spaces and making a case for them, Holy Rights silently reminds us that the collective fight finally is to make the world a safer and healthier space, and it can begin only by creating such small pockets of safe and loving spaces.

What one cannot ignore is how despite the intrusive nature of the camera, Farha still manages to create a safe space where the entire struggle reveals itself in all its complexities. The empathetic and sensitive gaze of Farha, her sympathy for women and their traumas, and the trust she builds with all of them is what creates the required safe space for the film to mediate the politics of the struggles, and also build the politics of the film.

If Safia and her husband’s relationship establishes a safe space for feminist politics, and the relationship between the women demonstrate the safe space for feminist praxis, then Farha’s craft exhibits the safe space of filmmaking for a kind of honest internal critique and solidarity amongst Muslim women, and the film as a cultural product aspires to create a safe space where an honest introspection could possibly occur.

It is only in such safe spaces that a religious Safia and a non-practising Muslim filmmaker Farha can come together, befriend each other, and become a part of the essential political action geared towards creating a healthy and safe space for all.

Through this, the film Holy Rights also tells us how for political action and social change, solidarity and political consciousness by itself isn’t enough. They have to be supported by a culture of love. The film also speaks how a political battle for equality cannot be fought overlooking the social battles and that the social battles cannot be fought overlooking the security of individual rights and building safe and loving spaces for individuals.

But then, as the final shot of the film says, at one level, these battles can feel lonely at times. However, the battle is also to fight political and personal loneliness.

Holy Rights recently won the Laadli Media & Advertising Awards for Gender Sensitivity-2020 and was officially selected for the International Film Festival of India, Goa. The film will also be screened at Women’s Film Festival organized by the Federation of Film Societies of India and to be held on 8-9 March 2021 in multiple cities (Bangalore, Pune, Hyderabad, Delhi, Jamshedpur, Thrissur, Imphal, Mumbai etc.).

Samvartha ‘Sahil’ is a student of life based out of Manipal, Karnataka.