“My writing is informed by personal, collective resistance:” Meena Kandasamy on genocidal violence against Tamils, poetry as resistance

In an interview with TwoCircles.net, writer, poet and activist Meena Kandasamy discusses Eelam struggle, Tigresses, Tamil nationalism, Dalit consciousness, poetry as resistance, her unconcealed writing style and more.

Shalini S, TwoCircles.net

Meena Kandasamy is an anti-caste activist, poet, fiction writer and translator. She has published two collections of poetry, Touch and Ms Militancy and three acclaimed novels, The Gypsy Goddess, When I Hit You and Exquisite Cadavers. She has also translated the works of Dr Thirumavalavan, Periyar’s Pen Yen Adimaiyanal (Why Were Women Enslaved), novelist Salma, and the Eelam Tamil poets V.I.S Jayapalan and Cheran Rudramoorthy.

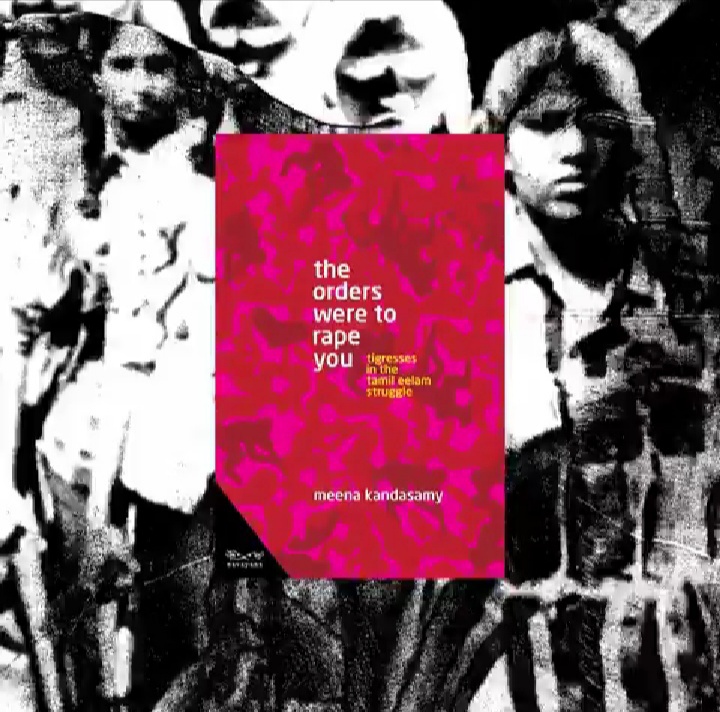

Her recent work The Orders Were to Rape You: Tigresses in the Tamil Eelam Struggle was first published as an essay in The White Review in July 2020, and earlier in February this year, the work took the shape of a book published by Navayana. The book is her impression of the genocidal war of the Sri Lankan state against the Tamils. Growing up in the period where Tamil nationalism was brimming, Meena Kandasamy has captured the violence and wartime rape faced by female fighters of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) through testimonies of Tigresses now living in distant lands as refugees. She also translates and presents the poems of three Tamil women combatants – Captain Vaanathi, Captain Kasturi and Aatilatchumi. One of the translated poems of Captain Vaanathi titled She, the woman of Tamil Eelam proclaims:

“On her neck, she wears not the thaali,

that marker of marriage,

but a cyanide capsule.

She embraces not men

but her weapons”

Excerpts from the interview:

The testimonies were gathered in 2013 to make a documentary. Why did you decide to publish it as a book and why the delay?

When this essay got published in The White Review, Navayana’s S Anand felt that a book will be accessible to more people and I was open to the idea because as a book it will also have longevity. The reason for the delay in writing this essay is that it took time for me to know if I have come to that place where I can write about it. When you are young, a woman and a writer, and start talking about self-determination, people will immediately label you a terrorist or a separatist. They are not interested in the legitimacy of the struggle. They are only looking to delegitimize it even before one starts writing. I also write in English. In Tamil, you can get on a stage and be supported. In English, there is so much gatekeeping against such a political idea. Once the documentary was made, there was a lot of going back and forth between countries. This story was always at the back of my head and I knew I had to tell it one day.

In the book, you talk about growing up with the posters of Tamil Tigers and Tigresses. Is there any particular incident that drew you towards their struggle?

I think it has more to do with the environment I was raised in. I was born a year after the July riots in 1983 and refugees had started coming into Tamil Nadu. There was a change in the political climate and its dynamics. I was raised in such a set-up and this is what people talked about day in and out. In that way, I was not just drawn towards it, but I could understand what was going on. Also, the mainstream Brahmanical media back then treated the Eelam struggle as a fringe element even though it was part of mainstream discourse. Irrespective of the narrative, the mainstream English media were spinning yarns about it. I felt that as Indians we had culpability in what happened in 2009 and I wanted to write about it alongside the backdrop of how we lived a second-hand war.

As an anti-caste writer, what do you think about the notion of Tamil nationalism affecting Dalit consciousness?

Firstly, if we look at the Vaddukoddai resolution dating back to 1976, the Tamil United Liberation front under the leadership of Thanthai Selva (S.J.V Chelvanayakam) not only talks about the self-determination of the Tamils but also calls for putting an end to the caste system. It was one of the earliest resolutions to discuss the caste system. Of course one cannot deny that there existed caste hegemony in Tamil Eelam but the Tigers were trying to structurally address it. LTTE Chief Prabhakaran was from the karaiyar (fishermen) community and Thamil Selvan, the head of the Political Wing, who attained the title of Brigadier posthumously, was a Dalit. There was leadership from below and it was the leadership of the oppressed. You could be among the tigers and rise to be the head of the political divide. These representations were not tokenism. It was a pluralistic movement and that is the reason why there could be leaderships from the most marginalised sections.

Secondly, the dichotomy between the Dalit movement and the Tamil self–determination movement is a very false binary. The Liberation Panthers or Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi modelled on LTTE and they do maintain a pan-Indian Dalit identity but it doesn’t prevent them from articulating about the rights of people of Tamil Nadu in India, and also the rights of Eelam Tamils in Sri Lanka. It is not a disjointed struggle. In both cases, you realize it is a Brahmanical state that has a foreign policy against the Tamils on the one hand and on the other hand has a domestic policy against Dalits. I cannot separate them and see them as antagonistic to each other. I do agree that natural questions of representation, of treatment of Dalits by everyone, including even the militant movements must be probed into, answered and documented.

Can you comment on the readiness of the female fighters to participate in the armed struggle?

The participation of women in the armed struggle was a choice they made for themselves. It was out of various complex reasons. It happened because rape was made a state policy by the Sinhala army and as a result of systematic discrimination against Tamil people, and as a question of what space did the Tamil society has for them and to even fight the patriarchy within the Tamil society. They wanted to come out of the oppressive position in which the general society sought to hold them. One-third of the fighting forces were women in LTTE. It wasn’t because of cohesion or brainwashing; it came from within. Joining a guerrilla struggle was how Tamil women were exercising their self-determination.

You write about the domesticated state in which the Tigresses are living in. Can you elaborate on that?

Domestication is something that happens to you when you are a refugee or an immigrant; there is no easy way in which you can go about representing your politics. You become a citizen living on the margins and it takes at least one more generation to enter into the national discourse of those countries. This is terrible because Tigresses, who were once making histories, were then starting a new life, getting an identity card, learning a new language, working night shifts at grocery stores arranging cartons or doing shifts at petrol pumps. I wanted to capture this tragic state of them in the book as well. This is the choice they have made because the other option would have been to stay home and get killed.

Can you comment on the razing of the memorial in the University of Jaffna and the UNHRC resolution?

There are extreme numbers of killings that have happened, the deaths that are not accounted for, disappearances, the whereabouts of people who surrendered with white flags. It is a burning question of justice. The figure is upwards of a hundred and forty thousand Tamils. It is not the genocidal killing and the extrajudicial murders alone, it is also about the question of what happened later in the camps and how women were treated. The Sinhala state must be held accountable for the genocide and war crimes, including rape and torture. I don’t think India has played a proper role in terms of its foreign policy where Sri Lanka is concerned. The ruling Union government has expressed much visible interest in Adani’s business and corporate profits on the island rather than the welfare of the Tamils.

There has to be a justice delivery mechanism even outside of institutions like the UNHRC. What we need in India is a national conversation about Tamil Eelam. India’s foreign policy and intervention are acts that have cast long shadows and for which Tamil–speaking people on the island continue to pay a price. As Indians, we have to hold India accountable, make India support and protect the Tamil people on a global stage.

On the razing of the memorials by the state, they want to eliminate any trace of resistance but I don’t think people will take it just lying down. People will keep protesting peacefully, demonstrations on women’s day by Tamil Eelam mothers and P2P (Pothuvil to Polikandy) march are instances of their fearless stance.

Why is poetry majorly used as a tool for political dissent and resistance?

I think poetry is very effective and powerful. It can make a statement. It can be easily consumed in the space of a classroom and in a short period. It can be performed on a stage or in a protest and it will make a statement. It can become political graffiti. But as a writer, I cannot reduce the multifaceted nature of a subject that I want to produce in other genres into a poem. One has to compartmentalize it accordingly.

Your works are unconcealed and are expressive of a woman’s body. How did you develop such a writing style?

I think it comes from political positioning. One of the problems with a lot of writing is that it tends to be neutral on everything. The general idea of a public intellectual is to be on the fence; the minute you have an opinion and identify with a particular movement, you are treated differently. A lot of my writing is expressive in a physical and a political way because it is informed by the resistance that is both individual and collective. On deeper reflection, the issues concerning women within caste patriarchy are subsumed under a sophisticated silence. It doesn’t get problematized or narrated. To initiate a conversation, one has to grab attention and you cannot do it with abstract intellectual jargon. You have to use people’s everyday language. The shock value comes when it is used in academic writings. Little do people realize that those are just words spoken on the streets and at home.