India and its two forgotten pillars of secularism

Secularity, according to both Ambedkar and Nehru, was innate to this new nation-state. One that was formed post immense religious dispute, the right for every religion to habitat and practice as they deem right - without affecting the rights of any other religion - was a fact that need not even be mentioned.

Oishika Neogi and Adil Amaan, TwoCircles.net

"But in politics, bhakti or hero-worship is a sure road to degradation and to eventual dictatorship." - B. R. Ambedkar

‘Secularism is not a happy word. It does not mean we are anti-religious, it just means India is not formally entitled to any religion as a nation’. - Jawaharlal Nehru

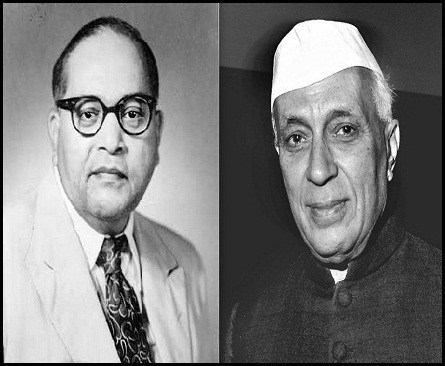

Two pre-eminent personalities of India gave their all to make the constitution peerless - one who drafted it with all his integrated thoughts and the other with a vision of implementing and executing in the roots of the nation. The first was born a Hindu but made certain he would not die as one; the second was not recognized as a Hindu by himself.

These two great visionaries were B. R. Ambedkar and Jawaharlal Nehru. Even though they harboured distinct ideologies, they had a unanimous vision of forming a Republic that was for all; one that barely paid heed to the religious or cultural identities of an individual but focused on the personal and social development of all of its citizens - the development of India. And for this vision - even though it has rarely been noted - they worked together in more ways than one.

Soon after Ambedkar died, speaking in the Lok Sabha, Nehru remarked that above all, he would be remembered ‘as a symbol of the revolt against all the oppressive features of Hindu society.'

After a few months of the Republic, these rights of all citizens were secured from any sort of discrimination by the state, on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth or any of them in Article 15(1) of the constitution.

Secularity, according to both Ambedkar and Nehru, was innate to this new nation-state. One that was formed post immense religious dispute, the right for every religion to habitat and practice as they deem right - without affecting the rights of any other religion - was a fact that need not even be mentioned. Opposing a majority of the Constituent Assembly, both Nehru and Ambedkar believed that a religious discourse had dominated the socio-political diaspora for far too long, and envisioned a nation-state that was beyond this conundrum. Religion, while was a right given to every citizen in the modern nation-state, could not dare be a factor influencing the politics of India anymore.

One providing the guiding philosophical leadership and the other appointed as the Chairman of the Constitution Drafting Committee envisioned one country. A country that was truly independent in every sense of the word.

Today, however, while we may be living in an independent nation-state, we have been repeatedly asking ourselves whether every person is all that free. Free to practice the fundamental freedoms the formative leaders of our country envisioned for us; free to perform our innate rights and duties. Religion, for one. The rights of religious minorities and voices advocating them have been categorised to be against the sovereignty and interests of the country itself. The tags of an ‘anti-nationalist or a ‘Jihadi’ have become more common than ever before. The absolute need to prove how Indian one is has become more imperative than ever before. The question of whose country is this, after all, has become more crucial than ever before.

Who is an Indian today? This question has become increasingly prominent in every spectrum of the country today - from social, legal, to of course, political. The nation, especially since 2014, has witnessed a stark increase in religious persecution. According to the Commonwealth Human Rights’ Initiative, apart from the Indian Penal Code offence that imprisoned the most number of citizens being those ‘against public tranquillity’ with a stark 86.2% in 2019, the past five years have been recorded with the highest number of Muslim detenues and undertrial prisoners with a shocking 70.8%. New religion-based legislatures have been passed and those in the minority have repeatedly asked where they stand in the Republic today.

The assertion of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) alongside the National Register of Citizens (NRC) in 2019 witnessed not just the minorities, but the entire nation asking that very question. The two citizenship laws - with the latter now not just applicable in Assam, but across the nation - together now legally stipulate every Indian to prove how Indian they are. Specifically Muslims. An Act protecting Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Parsis, Buddhists and Jains from religious persecution in three neighbouring Islamic nation-states before 2014, categorically excluded Muslims. It is then that a majority of the nation stood together and asked why? Where does a Muslim residing in the independent Republic for generations with poor documentation go? Why is it that only the Muslim community has been now asked to prove their birth, descent, registration, and naturalisation?

A government-led agenda that then witnessed mass protests did not just end there. For as recently as December 2020, we now stumbled upon a kind of legislature that was unheard of - the Uttar Pradesh Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion Ordinance, or more infamously known as ‘Love Jihad’. Preventing Hindu girls from being “conned and seduced to convert”, this new arbitrary anti-conversion law targets and criminalises specifically Muslim men for their sheer intent to marry in the majoritarian religion. With the Supreme Court ordering a stay on this law, this is where India stands today.

A country that was founded on the vision of not associating and promoting one religion over the other, what differentiates us from any other country that was not formed on the fundamental basis of secularity? Both B. R. Ambedkar and Jawaharlal Nehru, whilst not extensively speaking about this idea, made it distinct that India and its politics shall remain independent from the social divides that were already created before its creation. The vision was always to move towards a country that stood together upon just the principle idea of every citizen being an Indian. And today, with it soon being 73 years of the nation’s independence, we are increasingly moving further away from this dream. India today has taken a majoritarian face. The identity of our Rashtra (country) is fading into one - one that is not for all, after all.

___

Oishika Neogi and Adil Amaan are a Research Fellow and a Legal Fellow at Karwan-e-Mohabbat, Delhi.