By A Mirsab, TwoCircles.net,

Mumbai: In an attempt to advocate abolition of death penalty in India, the Asian Centre For Human Rights (ACHR) has, in a report, criticized the arbitrariness in awarding death sentences by the Indian judiciary and has categorically pinpointed flaws in sentencing death under the name of ‘conscience’.

The 77 page report released on May 25 ‘India: Death in the name of conscience’ examines the imposition of death penalty to convicts in the name of “collective conscience of the society”, which is often interpreted as the “judicial conscience.”

The report is being published as part of the ACHR’s “National Campaign for Abolition of Death Penalty in India” – a project funded by the European Commission under the European Instrument for Human Rights and Democracy – the European Union’s programme that aims to promote and support human rights and democracy worldwide.

ACHR report front page

The report specifically examines (i) manufacturing of ‘conscience’ to justify death sentence, (ii) the use of ‘conscience’ in the judgements imposing death penalty which have already been declared as per incuriam by the Supreme Court, (iii) how ‘conscience’, “which varies from judge to judge depending upon his attitudes and approaches, his predilections and prejudices, his habits of mind and thought and in short all that goes with the expression social philosophy,” plays out as to whether an accused charged with an offence punishable with death shall live or die, and (iv) inconsistency of the Indian judiciary while considering the factors and circumstances to determine between life and death in a capital punishment case.

The report is prepared after meticulous study of 48 Supreme Court judgements on death penalty pronounced by two distinguished former judges of the Supreme Court viz. Justice M B Shah and Justice Arijit Pasayat, who are currently serving respectively as chairperson and vice chairperson of the Special Investigation Team on Black Money appointed by the Supreme Court of India, to illustrate how ‘conscience’ of individual judges play out the ‘collective conscience’ and/or ‘judicial conscience’.

Per incuriam is a Latin term which means “through lack of care”. It refers to a judgement of a court that has been decided without reference to a statutory provision or earlier judgement which would have been relevant. The significance of a judgement having been decided per incuriam is that it does not then have to be followed as precedent by a lower court.

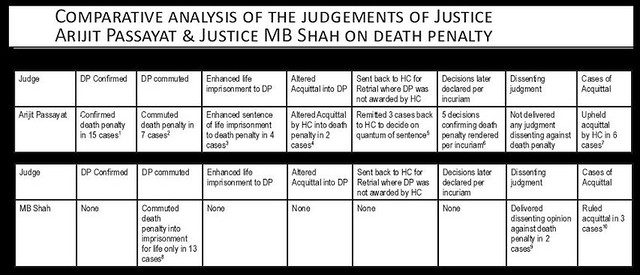

Out of the 33 death penalty cases adjudicated by Justice Arijit Pasayat examined by Asian Centre for Human Rights (ACHR), Justice Pasayat

(i) confirmed death sentence in 15 cases, including four cases in which lesser sentences were enhanced to death sentence and two cases in which acquittal by the High Courts were turned to death sentence,

(ii) upheld acquittal in eight cases,

(iii) commuted death sentence in seven cases and

(iv) remitted three cases back to the High Courts to once again decide on quantum of sentence as death penalty had not been imposed by the High Courts.

Interestingly, out of the 16 cases in which death penalty was confirmed by Justice Pasayat, five cases have since been declared as per incuriam by the Supreme Court.

On the other hand, Justice M B Shah did not confirm death sentence in any of the 15 cases of death penalty adjudicated by him. He rather commuted death sentence in 12 cases, did not enhance life imprisonment into death penalty in any case, did not alter acquittal by the High Courts into death penalty in any case, did not remit back any case to the High Courts on the quantum of sentence and did not deliver a single judgement, which was declared as per incuriam. He acquitted convicts in three cases out of which he passed dissenting judgements against imposition of death penalty in two cases.

Comparison tables

By comparing the reasoning of these two judges while dealing with death sentences, the report tries to prove how in India death sentence has become ‘judge-centric’.

The report says, “Whether an accused shall live or die has become essentially a matter of luck,” adding, similar disputation at other place: “It is troubling as it makes the life and death of a person dependent on sophisticated judicial lottery. These inconsistencies stand exposed on perusal and analysis of various judgements of the Supreme Court”.

Countering the main ground of ‘conscience’ in awarding death sentence, it says, “The reliance on ‘conscience’ for imposition of death penalty is deeply flawed, fraught with malafides at every stage, and is often manufactured through scapegoating of the dispensable i.e. the poor, socially disadvantaged and those accused of terror offences.” It added further, “They are often unable to defend themselves in all stages, most notably at the stage of the trial held under intense local social pressure, media trial and hostile environment.”

In regards with the terrorism related offences, the report says justice system has developed a clear precedent whereby the investigating agencies and prosecutors present evidence gathered under special laws such as TADA in trials conducted under the IPC to extract maximum punishment and the Courts embolden by ‘collective conscience’ have accepted the same without any qualm.

“This is nothing but abuse of the law driven by the desire for retribution in order to satisfy the so called ‘collective conscience’ rather than meeting the basic requirements of justice,” it speaks out for terror offences convictions.

In addition, it says, some crimes such as the ones against women and children are so gruesome and become politically significant in the light of massive public outrage that it almost becomes indispensable for the state/prosecution to find the guilty, even if it means tweaking justice, to assuage public anger.

As evidence it relies upon the documentary released in November 2013 on Arivu, in which the former Superintendent of Police of the CBI P V Thiagarajan admitted that he had manipulated Arivu’s confessional statement in order to join the missing links in the narrative of the conspiracy in order to secure convictions.

Listing much arbitrariness in various judgments dealing with death penality, it says Arbitrariness has been one of the grounds for declaring many laws as unconstitutional across the world and death sentences have been abolished on this ground alone in other countries such as South Africa.

“The situation and factors that were taken into consideration by the South African Constitutional Court for determining arbitrariness is not dissimilar to India – the mirror reflection is possibly worse in India. If death penalty can be declared unconstitutional on the ground of arbitrariness in South Africa, there is no reason why it should be constitutional in India,” the report concludes.

Asian Centre for Human Rights endeavors to promote and protect human rights and fundamental freedoms in the Asian region by undertaking range of activities. Details of their activities can be find at its website www.achrweb.org.