By Sibi Arasu for TwoCircles.net

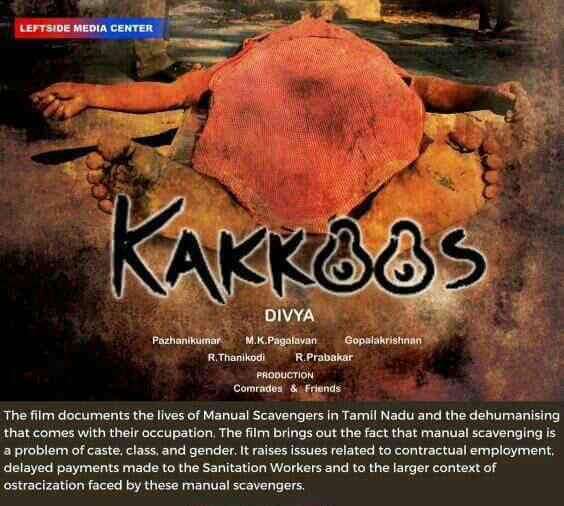

Strap: Kakkoos (Latrine) is a Tamil documentary that is a powerful indictment of society’s apathy towards the thousands who are tasked with cleaning public toilets and sewers. The filmmaker Divya Bharathi talks about why she made a documentary and what is the task at hand, post its tremendous success.

At last count, Kakkoos has had nearly 95,000 views on YouTube, even though it’s just two weeks since it was uploaded on the Leftside Media Center’s YouTube page. The film has been screened more than 200 times across the country in the last four months. Some of them being cancelled due to a threat of attacks by groups that were riled up probably by the ‘disgust’ the documentary brings to the fore.

The Safai Karamchari Andolan (SKA), the only group that vehemently lobbies for the abolishing of manual scavenging in India, claims that more than 1,300 people have lost their lives ‘during the job’. Bharathi alone has documented the deaths of 27 people in her film.

All of them because of a toxic combination of factors. An utter disregard for the life and safety of the manual scavengers (who almost always belong to downtrodden Dalit communities), penny crunching by employers resulting in the absence of the bare minimum of safety equipment and an utter desperation to earn that forces many into this job.

Bharathi, a member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) or CPIML says the reason for making the film was not to garner sympathy for the workers. Rather she wants Kakkoos to serve as a building block towards a concerted political process that would lead to the complete abolishment of this practice.

Appreciating film in Arupukottai

Born and brought up in a cotton mill workers community outside Arupukottai, about 60 km from the city of Madurai, Bharathi’s interest in film was nurtured even in this unlikely setting. “World cinema classics such as Bicycle Thieves, the hour of furnaces and Battleship Potemkin were screened in a film appreciation forum run by a comrade there,” says Bharathi. She adds, “Madhikannan, the comrade who organised these film screenings and more importantly, discussions where we deconstructed the film has helped shape my perspectives on cinema a great deal. I believe this also helped me in putting Kakkoos together.”

Bharathi also chose to make a film because she realized that it was the most effective way to get her point across. “I have read some great books, including a Tamil translation of Bhasha Singh’s Unseen, about the issue of manual scavenging, but no one spares the time to read now. Hence I decided to make a documentary about this instead,” says Bharathi.

A death in Madurai

“Even though I have been part of the Party and speaking up on injustice since middle school, I had never thought about this large group of people that you always see on the road,” says Bharathi. She is referring to the sewer cleaners and manual scavengers who are ever-present in urban spaces but despite or probably because of their ubiquity, they hardly seem to evoke any sympathy for their duress from others. “In October 2015, two men died while cleaning a public sewer and some other comrades were leading a struggle to get their family due compensation. I happened to take part in the protests and it was then that I realized that there was this huge group of people who we never think about. Who practice this inhuman profession and pay dearly every day for it, sometimes with their life,” she adds.

Bharathi said seeing Mahalakshmi, the wife of one the dead workers evoked something in her which was probably what made her so determined to begin this project. “His body was filthy, the mortuary staff refused to put his body in a freezer because he was Chakkiliyar (A Dalit sub group). None of us could even come near the body because of the smell of sewer and death. But Mahalakshmi was wailing and lying all over him and at moments talking with him as if he was still alive. This moved me immensely,” says Bharathi.

While they managed to get the legally sanctioned compensation of Rs 10 lakh through incessant protests on this occasion, Bharathi along with her husband and another comrade decided to document the lives of manual scavengers. “I pawned some jewels and well-wishers donated equipment. We started out with this and decided to document the death of seven men who had lost their lives under the sewer holes. As we continued though, it felt inadequate just to document their lives and not the hypocrisy of all quarters including but not limited to the government, NGOs, Feminist groups, Dalit leaders, Communist leaders and others when it comes to manual scavengers. This is what has made the film what it is today.”

A powerful reception

“The most engaging reaction to the film has come from people in various small cities and towns across Tamil Nadu and elsewhere who have seen it on YouTube. There are a lot of determined youngsters in the state today and I think they want to take this issue forward after watching the documentary,” says Bharathi. She adds, “This has been a great success.” Her plan now is to put together this ‘sense of action’ from various quarters into a coordinated political movement for the support of manual scavengers and ultimately to abolish the practice of manual scavenging. “A Tamil play was recently staged which was inspired by the film and many left parties have expressed their support in taking these people’s issues more seriously. I feel the documentary is achieving what we wanted it to do. The struggle now is to keep this momentum going,” says Bharathi.

Sibi Arasu is an independent journalist based in the Nilgiris. He tweets @sibi123.