By Abul Kalam Azad,

“History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce” – Karl Marx

Trumpets blaring, announcing the ending of a prolonged beginning! Delirious youth holding cans vomiting white dust, like blood of a snowy dawn. Booze unleashed on streets strewn with garlands, like colourful scars on stony faces. A person, visibly shaken with elation, beams, as if in a trance, that the wheels of time have turned and the leaders can no longer betray the ‘Hindu community’.

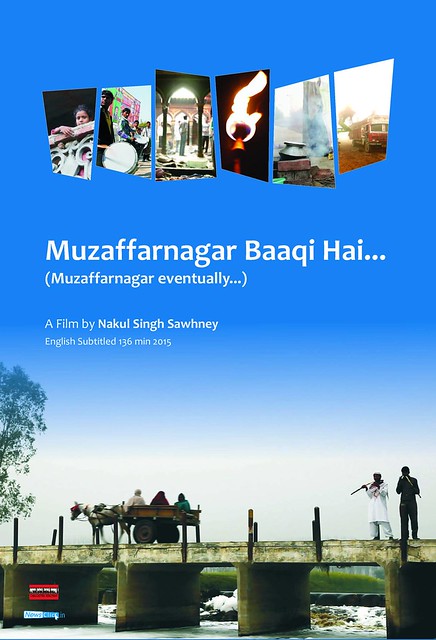

That was scene from a rally celebrating the victory, in 2014 Lok Sabha Elections, of riot accused BJP MP Sanjeev Baliyan in Muzaffarnagar. Few minutes into the extensive documentary, by Nakul Singh Sawhney , Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hain… , on the ghastly communal riots that unfurled in Muzaffarnagar district of Western Uttar Pradesh, during the months of August-September 2013.

My mind raced back, in a reluctant rush, to the eerily similar scenes, from the movie “Final Solution”, by Rakesh Sharma, documenting the Gujarat genocide of 2002. The vindication of their righteous rage! The Chaotic Jubilation! All bound together by this sustained hatred of a dreaded enemy. A re-enactment of a grotesque ritual!

I froze.

Close to 100 lives lost, more than 100 reported incidents of rape/gang-rape, most of them unreported, annihilation of homes, properties, livelihoods etc.- victims, and the victimised, being largely Muslims.

A large-scale displacement of lakhs – the internal refugees. Half-burnt leaves piecing together the remnants of their roots, they were able to drag on their broken backs.

A kid sketching, with her pencil, on her small notebook, the scene of the crime – circular faces, triangular roofs, and a bunch of huddled bubbles banging at the door: festering boils on the naked bosom of our ‘collective conscience’.

A father, sitting beside the grave of his one-and-a half year old child, who died of biting cold in the relief camps, and later, he, and his wife, watching a 20 second-odd video of their dear departed daughter on a tiny cell phone – perhaps, the only moving memory of that pound of their flesh they buried deep in the mud…

A man showing the charred remains of his scooter…an old woman, covering the lower part of her face with her dupatta, while recounting all that was snatched from her fingers; they destroyed everything, every single thing, she mourns with eyes which seemed on the brink of something steep, which she held onto with all the strength her grief could muster…women holding passport size photographs of their dead/missing loved ones…one wearing a blue t-shirt which resembled mine in my passport photo…that could have been me…my eyes closed, for a second. A scary second.

A tractor full of household items, of a migrating Muslim, returning to collect them, who said, with a straight face, that his neighbours did not even try to stop him.

Scores of angry, agitated Muslims, demonstrating, with many instances, of how this mayhem would not have been possible without the wilful negligence and apathy of the administration and the police.

Heart wrenching testimonies scattered like chalked clouds on this vast sky of sorrow that no single camera can capture.

File Photo of a burnt house at Lisad village of Shamli dist.

Sawhney’s film oscillates, back and forth, across time and space, theme and concerns…trying to forge a credible narrative from the ashes of this deeply conflicting past…layered at crucial points with a voice-over of the director, sounds of chimes and sometimes, a loud beeping sound, which disconcerts the viewer…as if someone is trying to relate a tale that is as difficult to tell as it is to hear…

As the film follows this convoluted maze, to make sense of why this “Mohabbatnagar” ( City of Love), the place known for communal solidarity, leaped into this burning cauldron of skeletons, an overwhelming aura of betrayal, and a hint of disbelief, maybe all this is just a nightmare, a very painful one, enveloped the Muslim community – the very people they talked to, played, worked and ate with, day after day, since ages, came one day banging at their doors, rounding up their homes, to burn them alive, to cut them to pieces, to rape and to loot…

Tracing the news in the local media, a few months before the riots broke out, made it abundantly clear that this was in the making long before it actually happened: the swords being sharpened well before the slaughter, the flames lit well before the funeral…the bogey of Love Jihad was being erected with the litter of random cases of molestations, a conspiracy created when there was one……the Maha Panchayats with inflammatory speeches, and young people, with swords in their hands, pistols in their pants, shook with rage, as if possessed.

Who was plotting this and for what?

Maybe, the answer hid in the elections. Or so thought the filmmaker.

He placed his feet firmly in the footprints left behind by the Modi wave. Linking, almost effortlessly, the entire turmoil to the electoral hopes, and the unprecedented victory, of BJP in a state that it has no significant presence before. Queue in the speech of Amit Shah, who managed the campaign in UP, ferociously proclaiming that this election was one that of honour: an opportunity to unleash their vengeance on the people exploiting them since decades, and a BJP leader shrieking, “ A Hindu never messes with one. If someone messes with him, he would never leave that one”.

One after the other, constructing the Muslim Specimen, customized to their wanton interests. The Muslim who kills our Mother Cow. The Muslim who explodes our population. The Muslim who lures our women..

The bearded Muslim

The terrorist Muslim.

The rapist Muslim.

An ironic, yet tragic, reversal of roles. Sword became the wound. Fire became the ash.

Shielded in this faux bubble of victimization, they left more and more victims in their wake…

As the Muslim leader of Bharatiya Kisan Mazdoor Manch, a breakaway faction of Bharatiya Kisan Union, whose platform was usurped by the Sangh, Ghulam Mohammad, reflects on how the ‘secular’ slogan of BKU “Har Har Mahadev! AllahuAkbar!”, morphed into “Har Har Mahadev!” and then the final leap into “ Har Har Modi!”..

The trajectory of Saffronization.

The crop of communalism ripe enough for the harvest of votes…

The edifice of ‘Acche Din”, its bricks cemented with communal divides.

The layers of patriarchy embedded deep in communal rhetoric was peeled with acute sensitivity: the issue of honour, the millstone tied to the throats of all women, and supposedly, the center-piece in the current spate of communal violence. Groups of assertive young women, mostly Hindu Jats, describing, with a matter-of-fact tone, in no uncertain terms, the differential treatment meted out to them at their homes since the time of their birth, the ubiquitous danger of safety they confront at each and every space, and, perhaps, most importantly, revealing that the major source of sexual harassment emanated, not from Muslims, but from within their caste, those that were close to them, and that the restrictions on their mobility starkly worsened post-riots. They disowned this flame of honour being passed onto their palms, questioning, why should women carry the burden of family honour, the same women they treated as inferior all their lives?

Something that went palpably missing in the documentary were the testimonies of the survivors of horrific sexual violence during the riots. Leaving out a couple or so references, pointing to the 180 odd rape incidents, of which only seven women filed a case, a discussion surrounding this aspect of the tragedy was largely, and unfortunately, absent. One can only speculate why the filmmaker did (or was forced to do) this. Women unwilling to share, owing to the stigma of rape/sexual violence, due to which most of these cases went unreported in the first place? Fear of retaliation?

Patriarchy- the pawn that never fails to deliver.

View of camp at Kandla.

One thing that goes regrettably missing in some discourses on communalism is the aspect of caste: both of the victims and the perpetrators.

But Sawhney doesn’t succumb to this irresponsible elision.

Although, Muslims, across caste and class lines, were adversely affected by the riots, there were also few, like a section of land-owning Muslim Jats in a village, who could return, with minimal damage due to their clout of power. It’s always the lower caste/class muslims who are the worst hit during such bouts of heinous violence.

The film also zooms into one of the few relief camps of displaced HIndus, inhabited by Dalits from a Muslim Majority village. Here, we could hear two people, convincingly declare that this time they would be voting for the BJP. However, later in the documentary, before the elections, some Dalits members of BSP refute this by reiterating that apart from a few chunks, Dalits shall always vote for their party. And a young differently-abled dalit, Vikrant, whom Nakul follows throughout the movie from then on, proclaims with pride, that Manyavar Kanshiramji has drilled into each and every brain of Dalits that they were not HIndus.

Sawhney underscores, with extreme care, a latent solidarity and empathy, albeit silenced ,that exists between these two communities.

An old Dalit, from BSP, opines, with a sense of sorrowful introspection, that Dalits have been oppressed by them (upper-caste Hindus) from 5000 years, now they are doing it to the Muslims, and Muslims are worse off than Dalits now, he says, where Vikrant chimes in citing the Sacchar Commission Report, which reveals the sharp decline in employment rates of Muslims since independence.

A Muslim, affected by riots, fears that now the Jats will move on to Dalits, having finished with Muslims, who were powerless and vulnerable. Another one, a farm labourer, laments that the Dalits he worked with everyday also joined the rioting mob, but then, he adds with a stroke of humbling kindness, that they have no choice but to obey the dictates of the landlord Jat.

Each reciting their own version of Martin Niemöller’s “Then they came for me”. In reverse. Me becoming them. Them becoming Me.

One really important aspect, that cannot be overlooked, in the fascist times that demand grave immediacy, is that the documentary never loses sight of the possible ways forward, politically. The debilitating violence of the past moves in tandem with the remedies of the future.

It seeks redemption in the Bahujan polity that would bring Dalits and Muslims, probably the communities worst hit under Hindutva regime, on one platform.

The film also never tries to obscure its working class sympathies in the cloak of neutral narratives. It stridently explores the devastating impact of riots on the farmers’/workers’ unions and their demands for fairer prices/wages, becoming weaker and weaker, by the day.

Sawhney meets the distressed sugarcane farmers, clueless about their struggles worsening more and more ever since the riots, who recount the times when they could get their demands met while they stood hand-in-hand with the Muslim comrades.

Throughout the movie, a small group of committed youngsters’, from Bhartiya Naujawan Sabha, walk through the mud streets of these villages, like the flickering light from a candle running out of wax. They engage with the people, spreading their message of communal harmony, through songs, demonstrations etc., always surrounded by a picture of Bhagat Singh hanging somewhere. They, painstakingly, persevere to point out to people that these communal disturbances are the weapons of the ruling class to divide the oppressed and, hence, divert their attentions from the ‘real issues’ of exploitation etc. But, dismissing religion and caste, nonchalantly as they did, as issues not real enough to fight for/against, has, traditionally, been the shortcoming of the broad Indian left, and hence, always failed to mobilize support for such causes. And, unfortunate as it sounds; these courageous young men are not exempt from this malady.

They patiently explain to a reluctant old man, presumably a modi-supporter, that this riot was orchestrated for electoral gains, and that the police/administration was hand in glove with it by pointing to crucial instances of their bias, of how they brought the situation in control few months back when news broke out of a Hindu man molesting a Muslim girl. But he was unconvinced. And he remained so, all throughout their interaction. He said, everything will be fine. As did many in this country, during the elections.

File Photo of a camp in Shamli.

The film makes an honest attempt to listen to the ever-intensifying concerns and fears of the Muslim community, which this violence, and the wider political response to it, exposes in stark lucidity.

A Mulayam Singh Yadav who shamelessly spews that the relief camps were a conspiracy of the BJP and Congress. A Rahul Gandhi who, with utmost insensitivity, hints that the relief camps were a breeding ground for the ISI agents. A Mayawati who doesn’t even visit the relief camps, which, Vikrant admits, after the electoral debacle, was a big mistake.

Then, why wonder when a young Muslim Journalist, from Muzaffarnagar, compares Muslims to potatoes- they are used by all, yet they taste/remain the same, no matter which curry is being cooked. The Potatoes in the curries of Indian Polity.

Then, why not sympathize with a Muslim student from Jamia, returning during the time of elections, regretting that despite all of us being humans first, it is becoming harder and harder for Muslims to be not painfully conscious of their religious identity?

“Are Muslims bad people?” The child of Shandar Gufran, returns from school, with this question.

Shandar Gufran, a Muslim educationalist, mourns how people he grew up with, his neighbours, his classmates, have slowly grown apart, how Naveen who was once his friend is just Naveen now, and how his is one of the few Muslim families still continuing to live in that locality,… not for long, though….

A community, vilified.

A community, alienated.

A community, ghettoised.

Sawhney, just before the ending, juxtaposes two adjacent, yet very distant, realities, equally dystopian: scenes from training camps of Sangh Parivar, where many Hindu children could be seen, with the tragedies of displaced, raped, angry, dead, and soon-to-be dead Muslims.

Pravin Togadia, with a hardly veiled grin, cautioning Muslims to remember Muzaffarnagar, even if they have forgotten Gujarat.

A VHP member saying that property rights for women is disastrous for the Hindu family.

A Modi supporter listing reservations as one of the top evils plaguing the nation.

Communal, Castiest, and Sexist.

The three faces of Brahma(nism)

But, what singed me hardest, in some frail corner of my heart, was the image of a living Muslim child lying, while playing, beneath the ground, in what seems like a grave the children themselves dug with sticks, which shall haunt me in the nights to come…

Children playing in make-believe graves

Children holding swords in training camps.

Perhaps, there is no better testimony for the fascist times we inhabit…

It ends, however, with a march where people holding flaming torches walk through the darkness of the night……

As the credits roll, a bunch of hopeful voices hum behind, the poem “Hum ladengey Saathi” by Avtar Singh Paash.

Sawhney sketches a honest portrait of a place whose social fabric torn apart by fascist forces lay tattered, like a corpse stinking on the streets, of the helpless sorrow weighing down the burdened wings of a population….

But, also, of the resilience of hope.

Hope of a return.

To normalcy

To dignity.

Eventually, this film reminds us to never forget Muzaffarnagar.

I write this, with many questions ringing in my nerves.

How long should a tragedy repeat itself to start smelling like bearable farce…How we halt the blood of history from spilling onto the streets of the future?

…………..

(The author is a student at the IIT, Chennai.)

Related:

Documentary on Muzaffarnagar riots screened at 60 venues across 50 towns in protest