By Syed Muhammad Raghib and Abhay Kumar for TwoCircles.net,

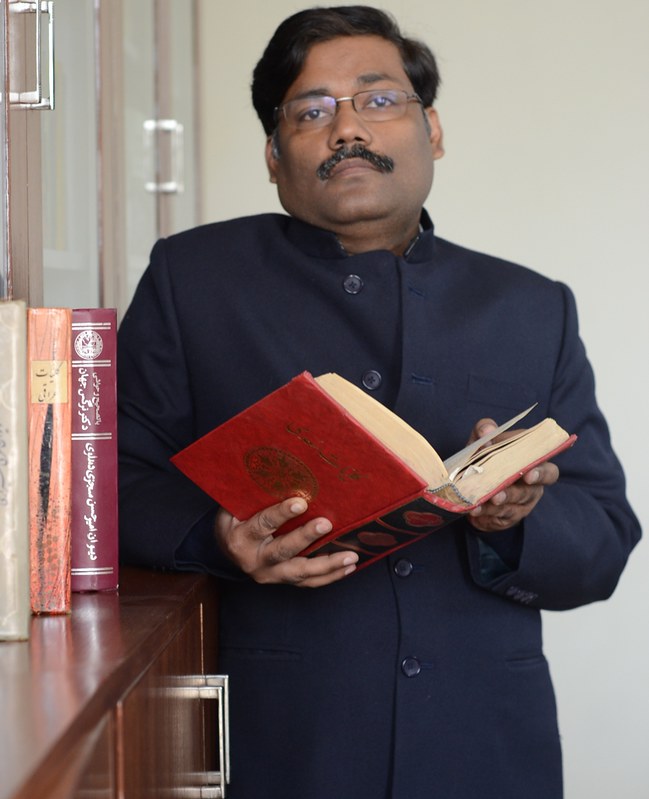

New Delhi: Akhlaque Ahan is an associate professor of Persian at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Author of over twenty books mostly dealing with history, literature, culture and religion, Ahan has expressed concern about the rising incidents of intolerance in India. Syed Mohammad Raghib and Abhay Kumar sat with forty-year old scholar last week to grasp the complexities of situations, following aggressive campaigns to polarise society and saffronise Indian history and culture. Excerpts.

TCN: Artists, writers, filmmakers, intellectual and others have returned their awards in protest against what they say are the rising intolerance in India. What do you have to say?

AA: Those who kindle hatred in society are in the minority. Even media feel inclined to cover their activities, giving the impression that the hatemongers predominate. But the reality is quite different. Those who voted for the BJP in the last General Elections were just 31 per cent of total electorates. We should not forget that those who supported the BJP in the previous elections do not approve of all of BJP’s policies. But one possible explanation of perceived predominance of hatemongers is due to the fact that secular forces are neither vocal nor united. For example, writers make up for a minuscule percentage of our population, but once they have started asserting themselves against intolerance, their impact has been widely felt. In short, people of this country are peace-loving (aman pasand) and the politics of polarisation and fear is pursued by those who want to divert nation’s attention from basic issues like education, health and employment.

TCN: The politics of “holy” cow seems to have polarized the society.

AA: It is unfortunate that cow is deliberately being made an issue in India. There is a ban on cow- slaughter in most parts of India. For example, the issue of cow was never taken up in Kashmir even during the days of militancy, though there has been ban since Ranjit Singh and Dogra period. Thus cow issue is linked neither to Muslims, nor to Islam. Even ulama [Islamic scholars] have spoken in favour of a ban on cow slaughter. Long back in the 1950s, Maulana Azad spoken in Jamiat Ulama’s meeting that Muslims should not sacrifice cows and none of them has dissented Azad’s views. Even the current president of Jamiat Ulama Hind had said that cow should not be slaughtered.

TCN: The rulings of the court in favour of having a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) have recently created concern among a large section of Muslims, especially religious scholars and community leaders.

AA: Uniform Civil Code is also one of those issues which are raked up to fool people. A false impression is created that this [UCC] is a Muslim issue. Those who are supporting uniformity should also bear in mind that Hindu society itself is diverse. Hindus from north India and south India have a lot of differences. That is why I argue that the Uniform Civil Code is an issue of the Government and not that of any particular community. Moreover, ulama should sit together to complete the work of codification as done by ulama of other countries. Such a tradition is also found in our own country. For example, in 1915 Maulavi Karimuddin codified Hindu Personal Laws. In those times, a large number of Muslims were scholars of Hindu texts and vice versa. Religious identity has never been a barrier of acquiring knowledge, and texts of different religions too have always been considered as the part of knowledge tradition.

TCN: Do you suggest that religious identity separates us today more than in the past?

AA: Much of the discourse based on religious identity was created by the divide-and-rule policy of colonial rule, which classifies ancient India as “Hindu” period and medieval India as “Muslim” period. It was the colonial rulers who used to give religious identity to languages too. For example, Arabic and Persian was linked to Muslims and Sanskrit to Hindus. But unlike such assumption of the colonial rulers, we have Amir Khusro and others who were experts of Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit. [Abd al-Qadir] Bada’uni, who is considered “conservative”, translated the Mahabharata and Ramayana from Sanskrit into Persian. In the 20th century, [Gandhian] Vinoba Bhave used to recite the Quran like a Qari of Egypt and wrote a tafsir [interpretation] of the Quran. Unlike our rich traditions, some narrow-minded people, under the influence of the British discourse, are causing damage to Indian civilisation.

TCN: In India, a considerable section of Muslims, their organisations perceive themselves to be backward. Do you share their concern?

AA: Education will spark off zehni bedari [intellectual awareness]. Thus, there is a need to initiate an educational movement. I always underscore the importance of education. All kinds of Muslim leadership; to say may be a mutawalli (trustee) of a dargah (shrine) and an imam of a masque as well as political leaders of the community–should give a call for acquiring education, which would be a great service to the community and nation-building.

TCN: Another issue linked to Muslim identity is Urdu. Government has been perceived to be discriminating it? Your take?

AA: Government’s support is not enough for the promotion of Urdu. The readers of Malayalam and Bengali are more sensitive towards their languages. A poet or a writer of Urdu gets his books printed and then feels contented to distribute them among his/her friends. The problem of Urdu lies much in readers than in writers. This is a challenge before Urdu speaking mass. It is a mere fallacy and historically wrong to associate Urdu or any other language with any religious community within or outside India. What about Tamil, Telgu, Kashmiri, Punjabi, Bangla etc?

TCN: How do you look at role of madrasa in the contemporary period?

AA: Grand Madrasas should prepare students to engage with intellectual and philosophical challenges, inter-faith debates and to counter ideological pandemonium. Today we do not have personality among ulama like Maulana Azad, Mahmood Hasan, Ali Mian Nadwi [Abul Hasan Ali Hasani Nadwi] and Maududi.

TCN: Opinions about madrasa modernisation are also divided.

AA: It is not true that changes have not been made in madrasa curriculum. In Nadwatul Uloom [Nadwa, Lucknow] a large part of old syllabus has been replaced and both Arabic and English are taught there. Similarly, in all madrasas attempts are made to incorporate modern educations too. As far as the standard of education is concerned, it varies from one madrasa to another.

TCN: As a teacher of Persian, how do you look at the recent move to remove Persian as a subject from service commissions’ exams?

AA: Separating a language from opportunities would certainly harm the prospects of the development of the language. Languages like Pali, Sanskrit and Persian which are sources of our modern languages, culture and history should be studied and safeguarded. No language should be linked to any religious identity. Both Sanskrit and Persian are sister languages. One should not forget that Persian has rich sources about any aspect of Indian history. For example, to write about the history of Sikhism and Hinduism, or Indian culture, art and any facet of our civilization, scholars have to consult Persian sources. The personal diary of Ranjit Singh [the founder of Sikh Empire] was written in Persian and so the whole history of the region. Persian was the medium through which Europeans came to know about Sanatam Dharma and Indian philosophy, thanks to translations done by Dara Shikoh. One cannot comprehend Tagore without knowing the Persian legacy that he inherited. Even the term “Hindu” has a Persian origin. That is why the act of not studying Persian will only cause damage to our own civilisation.

The interviewers—Syed Mohammad Raghib ([email protected]) and Abhay Kumar ([email protected])—are both Ph.D scholars at the Centre for West Asian Studies, Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, respectively.