Book Review: A Heartbreakingly-powerful Memoir of a ‘Normal’ Muslim

‘I would have no explanation if God forbid, I got arrested.’ The line from Neyaz Farooquee’s memoir ‘An Ordinary Man’s Guide to Radicalism: Growing Up Muslim in India’ succinctly captures the dilemma and fear of young Muslims.

By Afshan khan

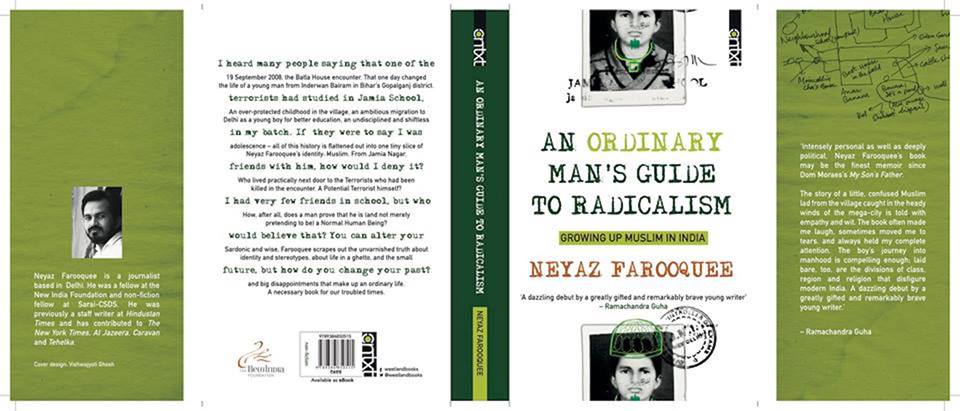

Book Title: An Ordinary Man’s Guide to Radicalism: Growing Up Muslim in India

Author Name: Neyaz Farooquee

Publisher: Context – Amazon Westland

Year: 2018

On first impressions, it seems that journalist-turned-author Neyaz Farooquee’s memoir, An Ordinary Man’s Guide to Radicalism: Growing Up Muslim in India, is all about the infamous Batla House Encounter that took place in September 2008. I, in fact, harboured the same impression until I started turning the pages of Farooquee’s debut work. i realised that while the book obviously centres on the encounter that many believe was fake and its immediate aftermath, Encounter is a pivot around which several narratives are built, explained and realised.

In the book consisting of 18 chapter, Farooquee talks about his own experiences of his childhood in Bihar, his school, and how he moved to Delhi in pursuit of higher studies at the young age of 10.

Once he moved to Jamia Nagar, a largely Muslim-concentrated pocket in Delhi located around Jamia Millia Islamia, his life appeared to have settled. Farooquee took admission in one of Jamia’s schools and studied in the same university till post-graduation.

Growing up as an overprotected child and a bold boy, Farooquee soon turned into another Muslim boy under siege especially after the fateful police shootout in September 2008.

In the aftermath, he was scared to think what would happen if he too was arrested, or worse, killed in another encounter.

Ten years ago, the Batla House Encounter in September 2008 had brought global, albeit mostly unwanted attention towards the locality. The encounter of the two young Muslim boys in Batla House locality raised questions on the intentions of security agencies and the government. Many in the locality suspect that the encounter was staged.

One of the boys killed in the shootout, who was allegedly an Indian Mujahideen terrorist, was a student of Jamia Millia Islamia. Soon, over-the-top media coverage painted the entire university and the locality as ‘hub of terrorism’, creating panic among students and local residents.

The fear was not completely unfounded. Farooquee elaborates on how there were several reports of police, often in plain clothes, picking up local boys. Several others were detained for questioning for any direct or indirect link with those two killed or other alleged IM operatives arrested in days to follow.

Locals felt helpless as they lost faith on police while none of the leaders of even the so-called secular parties, most importantly the Congress, that was in power both in Delhi and at the Centre, was willing to hear them. In those moments of crisis, local imams and clerics, often branded as extremists, played a very critical role, appealing to maintain peace and stay calm. Farooquee talks about how his friends told him that the Imam spent a long time making a dua during the afternoon prayers. The Imam said,' If the young men were indeed involved, they must be punished' and everyone said 'Ameen'.

'Many masjids, along with the call to prayer, asked the residents to stay calm.'[P:95] They announced, 'It's the month of prayers and compassion and mercy. God sees everything. And He is Just.'

The author was in the final years of graduation at the time of the encounter, and luckily was not once stopped by the police or questioned. The palpable tension and dilemma, the helplessness he still went through, only gives a glimpse of what living as a perpetual suspect means.

The book also gives a great insight into the ‘steps’ that Muslim youth take to shed themselves of any possible investigation. Farooquee ‘unjoined’ and ‘unfriended’ all the groups and individuals that might remotely connect him to terrorism, on the then popular social media platform Orkut. He cleared all his messages, contacts and every possible means through which police could make a ground for

his arrest.

The 2008 Batla House encounter changed the locality and its residents forever. After an initial period of staying quiet and laying low, many residents eventually came forward and volunteered to shed inhibitions and tell their stories in their own ways.

Put simply, the book is about how different circumstances moulded an individual, particularly a Muslim in India, and how they change the way they perceive the world. That way, the book is a glimpse of Jamia Nagar’s ‘world view’ through Farooquee’s eyes.

Farooquee was a student of Biosciences, but he decided to pursue journalism for masters after the extremely problematic coverage of the event in all formats of media that framed the entire community as potential terrorists.

He also mentions about some of his peers who their own ways worked towards bringing truth to the fore. A senior from university, and then student of mass communication, Afroz Alam Sahil filed several RTI applications to all possible departments, including Delhi Police, AIIMS, NHRC, etc. to finally obtain copies of post-mortem reports of those killed in the counter, including Delhi Police Inspect M C Sharma. Post-mortem reports got wide coverage in media, strengthening people’s doubts on the encounter.

Besides the encounter, the book also touches upon different issues gripping the Muslim community through the eyes of a college student. It mentions about the purported fatwa against Salman Rushdie and how Professor Mushirul Hasan was dubbed as his supporter for upholding creative freedom.

The book is sprinkled with verses from Mohammad Iqbal, Kabir, et al that Farooquee heard from his grandfather. He mentions about how Iqbal’s Shikwa (lament) to God that got him the wrath of clerics, forcing him to write Jawab e Shikwa (Response to Lament), that earned him the title of “Allama”. Iqbal also sang Saare Jahan se Achha and wrote Naya Shivala.

Reader might think that he has overloaded the book with his personal and family life details and references to the poetry by Iqbal, Khusrau etc., but the message of the book wouldn’t have been complete without doing that. Through those anecdotes and stories, Farooquee successfully gives a peek into lived experiences of an ordinary Muslim who also live like any other normal human being.

The book in fact prods readers to question the general stereotype they build for Muslims, that makes even ‘normal human beings’ become victim of circumstances. It plays on these two words – normal and ordinary – beautifully to drive home the point.

Writing a book on stereotyping of Muslims in these crucial times when voices of marginalized are being withered, is a highly appreciable and courageous, and recommended for understanding the minds of young Muslims.

(The author is a Delhi-based Journalist.)