(Editor’s note: This was first published on Yahoo.com as a single piece. We are reproducing the long form report in parts for TwoCircles.net readers.)

You are 13, kidnapped from your street along with three friends, drugged, raped, and dumped 150km away. No one could possibly blame you, but they do. The authorities investigate you instead of the accused men. What appeal does a young Dalit girl from Bhagana, Haryana bring to a nation that thinks it has now become sensitive to sexual assault? Is it enough to live on the pavement at Jantar Mantar for months on end, hoping someone will notice your call for justice? How long will your fight for a new life last?

A Portrait of the Indian as a Young Dalit Girl: Part 1 – The PlaygroundA Portrait of the Indian as a Young Dalit Girl: Part 2 – Sisters, MothersA Portrait of the Indian as a Young Dalit Girl: Part 3 – Meeting Janvi

By Priyanka Dubey

People of Dalit communities from Bhagana village outside the Hisar mini-secretariat. They have been camping since 2012, protesting the unequal land distribution and social boycott by the Jats in their village. Photo by VK Singh.

In a little while, Janvi and the others wake up. She adjusts her green dupatta and smiles in greeting. They make space for me and we sit watching the rain. And that evening for the first time, Janvi goes into a detailed description of events of the night of March 23 as Sushma and Leela look on.

“My exams were going on and that evening I was trying to study. Then around 8 pm, I stepped out of my house to pee. Meena, Sushma and Leela used to live in my neighborhood and we often used to go pee together. That night also, all four of us stepped out and just a little distance from our houses, a big white vehicle stopped in front of us. There were five Jat boys in that car. I immediately recognized three of them. They were from our village. They called out to Meena. She refused to go and they started pulling her inside. When we tried to stop them, they pulled all of us inside the car.”

“They held a cloth in front of our mouths. It had a strange cold smell. I began losing my consciousness slowly soon after. I was carried away to the fields by the boys. I remember someone touching my body; I felt the hurt and the changing weight of bodies over me. But I was not in a position to resist, to shout or to even open my eyes properly. It was hazy and then I completely blacked out.”

“When I woke up the next morning, Meena, Sushma and Leela were lying next to me. I remember when I first tried to get up, my arms and stomach started aching a lot. I felt a very heavy and piercing pain below my stomach as if somebody was hammering a nail on a wall. I also felt hurt on my cheeks, jaw-line, scalp, shoulders and legs. I was at a railway station (later I realised we were at Bhatinda station), I was so baffled and scared by what might have happened to me that I started crying.”

As Janvi and the girls speak, we realize a handful of men passing by in the rain have stopped and are trying to overhear our conversation. I ask the men to leave. Seventeen-year-old Sushma says, “By now, we knew that we were raped. We could just feel it in our bodies. We were in pain and were still feeling dizzy. Even the Punjabi people standing around us realized that something terrible had happened to us. We understood that we were far away from our village, in Punjab now. We tried to ask them how we could reach home, but we did not understand each other’s language. They spoke Punjabi and we talked in Haryanvi.”

A detail they barely registered at the time was this. Meena had woken up to find a phone tucked into the neckline of her kurta. “We didn’t know what to do. But a few hours later, we saw our fathers with the sarpanch coming towards us.”

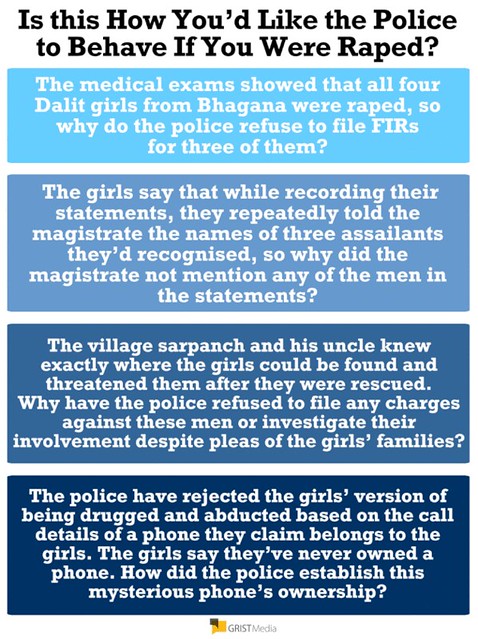

How did their fathers know where the girls were? This has been one of the strangest, most terrifying aspects of the case.

On the night of March 23, 2014, the fathers of all four girls went to the sarpanch’s house, as they do in all emergencies, and told him that their daughters were missing. As Janvi’s father Lakshman told me later, “He asked us to drop the idea of going to the police and told us to wait till morning. He said that our daughters would return the next morning, and going to the police would bring us a bad name.”

“We were restless, but we went back home. All of us went to him again the next morning. This time he told us that he knew the exact location of our girls. After that, he hired a big car and took all of us to Bhatinda. He took us to our girls who were sitting at Bhatinda Railway Station.” Sarpanch Rakesh Panghal later told me that the Sumit Panghal, the prime accused, had told him the exact location of girls over the phone.

They travelled back together – the girls, their fathers, the sarpanch and his uncle Virendra. In the car, the girls cried quietly. They were still in pain, dizzy and sleepy. They reached Hisar around 10 pm on March 24. In Hisar, the girls say, the sarpanch stopped the car at a restaurant. He made the four girls eat on the first floor of the restaurant. At this point, Leela in a tight angry voice describes the first of the incidents that indicated to the girls that their troubles were not over. “While our fathers were eating downstairs, he came up and threatened us. He said that if we took his or any of his family’s or Jat community members’ names in this incident or dared to complaint about what had happened to us, he would kill us immediately. He also said that he would kill our parents and that he could very easily destroy our families at any time.”

For the rest of the week, the girls and I talk. On one of those days, we turn to what happened when they reached home. Sushma says, “At home, our fathers were very worried because they wanted to file a complaint with the police and at the same time, they also feared a brutal backlash from angry Jats. Had this happened to just one of us, they would have never gone to the police. But since we were four girls from different families, all the Dhanuk men from our village collectively decided that we would file a complaint. The sarpanch and his men tried their best to stop us from filing a case.”

“On the morning of March 25, somehow we reached Hisar’s Sadar police station with our fathers,” says Sushma. The Hisar police sent all four girls to a local government hospital for medical examination.

Janvi remembers that day as one of the most painful days of her life, no less than the crime she survived on the night of March 23. “That day, we reached the hospital at 10 am in the morning and were asked to sit on a bench before the tests began. The whole morning passed, then afternoon passed and then evening passed and nothing happened. We kept on sitting there hungry, sleepy and silently crying in pain. But no doctor came.” Meena was the first to be examined – at 11.30 that night. “I was examined post-midnight. I was already sleepy and in tears when I went to the doctor.”

After delaying the girls’ medical examination for a whole day, the police then did a shocking thing. They insisted on taking the girls’ statements in front of a magistrate right then in the middle of the night – a procedure usually followed only if a victim is on her deathbed.

Janvi says, “Our statements were recorded between 1.30 am and 3 am. I don’t clearly remember what I said in my statement because I was very tired, too hungry and sleepy to understand anything. My whole body was aching with pain. Around 3.30 am, the cops left us outside the magistrate’s home and went away. It was raining heavily and I was crying. I don’t know how our fathers brought us to the protest camp situated in front of Hisar’s mini-secretariat where our people were (camping). I reached the camp and immediately fell asleep on the ground.”

An FIR was filed on March 25 at the Sadar police station of Hisar against Sumit Panghal, Lalit Panghal, Sandeep Panghal and two unknown persons. By April 1, police arrested the three named and accused along with two more – a man named Parmal and a juvenile who was later released on bail. The five Jat boys from Bhagana were booked under Sections 363, 366, 366A, 376, 120B and 328 of Indian Penal Code. Besides, charges were also leveled under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 and the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989.

The FIR counts 18-year-old Meena as the only victim of the Bhagana gang-rape. Along with the FIR, the statements recorded under Section 164 of the CrPC also say that all the girls apart from Meena were not conscious, and do not know what happened to them on the night of March 23. The medical examinations of all four girls confirmed rape. This is why for months, the Bhagana Kand Sangharsh Samiti has been demanding that the statements of all four girls should be recorded afresh in a fearless, healthy environment. And that the complaints of the other three girls should be added to the FIR.

*Names of all rape survivors and their relatives have been changed.

(Republished with thanks to Yahoo.com, Grist Media and Priyanka Dubey)

Related:

A Portrait of the Indian as a Young Dalit Girl: Part 1 – The PlaygroundA Portrait of the Indian as a Young Dalit Girl: Part 2 – Sisters, MothersA Portrait of the Indian as a Young Dalit Girl: Part 3 – Meeting Janvi