By Waseem R.S

“Krishna, what is the case with your grave?”

I asked suddenly and he replied, excited. “We won in the High Court, Bhavanechi”

“What do you mean?”

“We are laying the foundation after we have the palukaachal”

I was shocked, “So the grave?”

“There was no grave, that’s just some myth”

(KR Meera, Khabar)

Khayaluddin Thangal, the protagonist of KR Meera’s novel, lost the case to his grave on November 9, the same day that the judicial system declared its ‘final judgement’ on the Ayodhya dispute. Khayaluddin had claimed that the grave belonged to his ancestors who had converted to Islam. The ‘secular courts’ in India pronounced that Hindus were entitled to the land that they ‘believe’ was “Ramjanmabhoomi”. Hashim Ansari, the first complainant against the construction died on the day of the verdict, aged 92. Khayaluddin, the protagonist of ‘Khabar’ also passes away on the same day from brain-death. The news of shattered justice or green injustice must have caught them off-guard, must have been too much to take. As another December 6 passes, only vague memories remain.

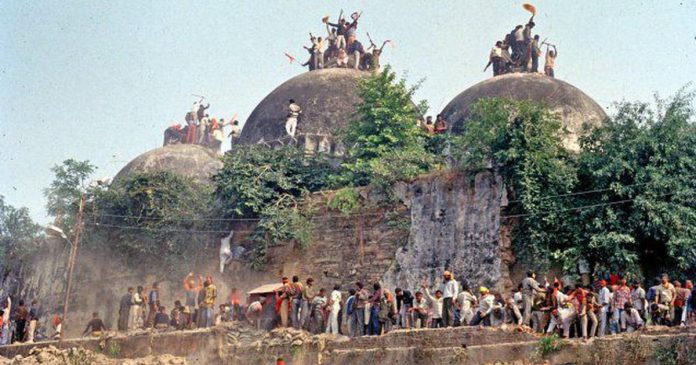

On December 22, 1949, statues of Hindu deities appeared unexpectedly inside the Babri Masjid. Rumours abound that it was no ‘miracle’, but a coordinated attempt with the knowledge of the mainstream political leadership. When the Sangh Parivar demolished the mosque, it was reasonable to assume that God wasn’t blind and that justice would be rendered. But after 27 years of the “most controversial case” in Indian legal history, justice has become an ‘elusive’ word for Muslims. The wounds inflicted through Babri’s desecration have still not healed for many. But nevertheless, Hindus were overjoyed, there was secular silence.

Shabnum Tejani argues that the demolition of the Babri Masjid was aimed at undermining the Bahujan politics that had emerged in the wake of the implementation of the Mandal Commission report. VP Singh’s decision to implement the recommendations was followed by a 10,000 km rath yatra. The Sangh Parivar sought to eradicate Bahujan mass politics and its struggle for equal rights. It was an attempt to ethnically stir up people and establish a Hindu vote bank and the illusion of a “Hindu Unity” through Hindutva ideology. This was undoubtedly the aim of the rath yatra led by LK Advani, Uma Bharti and Murli Manohar Joshi. As noted by Ashok Yadav, some Dalits sadly chose the day of Bhim Rao Ambedkar’s death to demolish the Babri Masjid.

The demolition can be seen as a spectacular event that it is part of psychological warfare against the Bahujan masses. Rather than focus on internal caste contradictions, it attempted to placate ‘internal’ divisions by framing an ‘external’ enemy of the Muslim. When the Babri Masjid was demolished on December 6, 1992, and about 150,000 Karsevaks laid the foundation stone, their goal was to build a nationwide Hindutva mass movement. The ensuing anti-Muslim riots were deliberate, in their script, to produce the enemy.

Socially, politically and even morally, the demolition of the Babri Masjid has strengthened Sangh Parivar organizations like the RSS, VHP and the Bajrang Dal. But even secular parties, including the Congress, did not address the political crisis that the Muslim minority underwent. What’s more, even the CPM’s stance, which is critical of the Congress, evolved to blame the victims. EMS Namboothiri immediately after the demolition of Babri Masjid issued a statement to “dissolve the Muslim League” as the RSS, being the binary opposite of the League, somehow contradictorily also ‘nurtured’ it. Hilal Ahmed, after much research in the area, pointed out the mistakes of the Congress and the Left in their approach to Muslim politics that emerged during the post-Babri period. In Kerala, the Congress, however, changed its view on the Muslim League, albeit slightly. The politics of Muslim representation in post-partition India has been about learning new languages of cultural and social rights struggles. What’s more, they are part of movements that play a major role in the struggle against the central government. Peasant agitations, critiques of upper caste reservation and the agitation against the Citizenship Amendment Act were found strong grounds in the realm of Muslim minority politics.

Nevertheless, there is no doubt that Muslim politics has structured its positions in a ‘defensive language’, often limited by constitutional and legal frameworks. It is in terms of being a minority that Muslims have raised their cultural and social rights in the name of democracy. But Muslim politics has always had to accept the blame for ‘outsiders threatening India’ when it comes to raising issues of Indian nationalism. But one of the cornerstones of political representation by Muslims is the attempt at perseverance and resilience which has probably never been taken up by other community organizations. Muslim political representations raised the narrative surrounding Babri Masjid and rights as through constitutional and legal means. But where such rights politics itself fails, it is not only the ownership of the Babri Masjid that is in crisis but also minority rights to political constituency itself in Indian democracy.

The impact of the demolition of the mosque with the tacit approval of the government, the acquittal of the perpetrators of the Babri Masjid demolition and the Supreme Court’s decision to allow the construction of a Ram temple at the site of the mosque have had a profound impact on the already weak Muslim minority. It is noteworthy that the court also adopted the dispute resolution approach put forward in 1985 by ‘Organizer’, the front page of the RSS. The fact that the RSS’s claim at the time that the Hindu community could contribute and give the opportunity to build a mosque elsewhere was legitimate is a clear message. The way forward is potentially confronting what awaits us, as we live through the darkest times of democracy.

Waseem R.S. is a Phd student at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.