By Ayub Khan for TwoCircles.net,

The dark clouds of communal violence are once again hovering over the city of Hyderabad. In what has become a trend since the 1970s whenever there is political uncertainty in the state, Old Hyderabad is used as an arena to flex the power of various political parties, their factions and the affiliated gangs of musclemen and goonda elements.

The latest bout in this saga has been triggered by what have been termed as attempts to illegally expand the temple located next to the iconic Charminar leading to structural damage to the latter. The conflict has now become a battle of one upmanship among various communities and interests aiming to gain political and economic supremacy in the city as well as in the state. It is being alternatively being played out in the streets, media as well as in the courts with the Andhra Pradesh High Court ordering that the status as of October 31, 2012 be maintained and that no further alteration or expansion work at the temple be allowed. Lost in the claims and counterclaims of the various protagonists in the ensuing conflict is the historical facts and this article intends to shine light on this important facet.

An undated post card of Charminar issued by the Advertising Branch, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of India.

Charminar

Charminar, as is well known and established, was constructed in 1591 by Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah. There is scholarly dispute about the reasons behind its construction. One claim is that it was built to commemorate the end of a plague in Hyderabad as it resembles a tabut (wooden coffin). According to this version processions of tabuts and alams were taken out during the plague and Charminar was supposed to serve as its lasting reminder and to be thankful that the calamity has been cast off.

According to another version it was built for the purpose of serving as a madrassa. The existence of student cloisters & a mosque in its upper floors strengthens this assertion as has been mentioned in the earliest extant works like the Tarikh-i-Muhammad Qutb Shah (1617) and Maasir—i-Qutb Shahi (1629).

A third view forwarded by Ghulam Yazdani, who founded the archeology department of Hyderabad in 1914, is that Charminar served as a majestic gateway to the royal palaces then located in its vicinity.

Regardless of the purpose behind its construction there is absolutely no mention anywhere of the existence of a temple anywhere in close proximity to Charminar. Similarly, neither the French traveller Jean Baptiste Tavernier, who visited the city in 1652, nor Abbe Care, who came in 1672, mention the existence of any temple. Much closer to our time Syed Ali Asgar Bilgrami’s comprehensive Landmarks of the Deccan: A Comprehensive Guide to the Archaeological Remains of City and Suburbs of Hyderabad (published in 1927) also draws a blank about the existence of any temple.

The coins and stamps of Charminar issued under the Asaf Jahi Dynasty also do not indicate any temple. In the light of the dynasty’s adherence to the syncretic culture with which it prided itself it is surprising that they would have neglected to indicate had any such structure existed.

A poster issued in 1970s by the Ajanta press

A 1942 issued coin showing Charminar

The Mysamma Stone

Many old Hyderabadis who have seen the era testify that up until the early 1950s there was no Hindu shrine near Charminar. In the latter part of that decade, however, a small corner stone of the structure began to be regarded as Maisamma, a local deity worshipped in the Telangana region. An old lady, reportedly dalit, used to sit near it collecting money and applying kumkum over it. This is mentioned in a report published by the Centre for Social Knowledge and Action in 1984. The report described how attempts were made to make Charminar a contested space in 1979 when a truck, according to other reports a Road Transport Corporation bus, knocked down the stone leading to communal tension.

Immediately afterwards the Marwaris in the area installed an idol of Mahalaxmi and built a small enclosure around it. It was reportedly desecrated several times in 1979-1980 (Apparently,’ people lost count of how many times it was destroyed and rebuilt’). But each time it was resurrected with a larger structure. The report says that some observers saw the ‘jittery hand’ of the ruling government behind the whole affair.

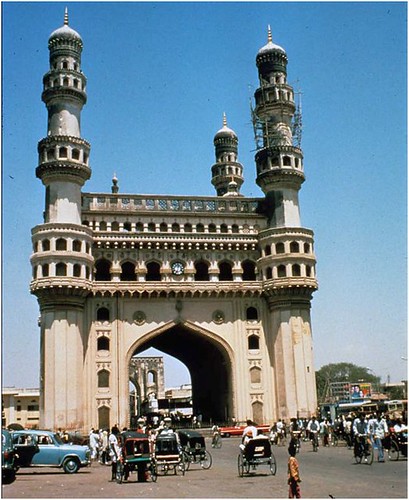

A picture of Charminar taken by the late Dr. Omar Khalidi in 1986

Who is it dedicated to (Maisamma, Mahalaxmi, Bhagyalaxmi)?

In the light of the prevailing sentiment then it is surprising that the Telangana protagonists allowed a shrine dedicated to a local deity being appropriated by the settler Marwari community. The lack of an organized dalit movement in the city and state at that time might explain for such easy appropriation.

As is well known the Marwaris are a business community who are great devotees of the goddess of wealth and therefore they called their new structure as Mahalaxmi Mandir. However, in the 1990s, in the backdrop of the Babri Masjid controversy, they surreptitiously renamed it as Sri Bhagyalaxmi Mandir. By this they disingenuously tried to link it to Bhagmati, who in popular belief was a dancing girl in whose love Quli Qutb Shah founded the city. But this assertion is untenable on many counts. The existence of Bhagmati is in itself of serious historical dispute with some prominent historians discounting her existence. Secondly, even if she existed her name was Bhagmati and not Bhagya Laxmi.

The role of superstition

The role of superstition cannot be discounted in these competing claims over Charminar. The inscription of Charminar on the Asaf Jahi coins had led to belief among common folks that it is the ‘daulat ki devi’ or ‘goddess of wealth’ and that Hyderabad’s fortunes are tied to the monument. Similarly, rumors were spread that clanking (cham cham) noises were heard at the monument at the middle of the night indicating that it is a storehouse of hidden wealth. That these beliefs might have a role to play is indicated by the fact that a large number of Marwari and other women from North Indian business communities (as indicated from pictures showing their unique style of wearing sarees) lined up at the temple in long lines earlier this week despite the tense and dangerous situation.

What Next?

A great game is being played in Hyderabad by those in power to further their political ends. Caught in is between is a monument which symbolizes the city. It has been a unifying structure for people belonging to all castes and creeds. Now it is being turned into a contested space. Would the citizens of Hyderabad stand up and say no to the agents of hatred and divisiveness? What role do the government and the judiciary have to play? And what about the callous behavior of the Department of Archeology which has been caught napping while the encroachments were happening? Will it at least now wake up from its slumber? The answers to these questions are all too apparent for those willing to carry out their duties and save the city.

Related story:

Charminar, once an icon of Hyderabadi pride, now a combat ground of religious dominance